Design Patterns for Securing LLM Agents against Prompt Injections

13th June 2025

This new paper by 11 authors from organizations including IBM, Invariant Labs, ETH Zurich, Google and Microsoft is an excellent addition to the literature on prompt injection and LLM security.

In this work, we describe a number of design patterns for LLM agents that significantly mitigate the risk of prompt injections. These design patterns constrain the actions of agents to explicitly prevent them from solving arbitrary tasks. We believe these design patterns offer a valuable trade-off between agent utility and security.

Here’s the full citation: Design Patterns for Securing LLM Agents against Prompt Injections (2025) by Luca Beurer-Kellner, Beat Buesser, Ana-Maria Creţu, Edoardo Debenedetti, Daniel Dobos, Daniel Fabian, Marc Fischer, David Froelicher, Kathrin Grosse, Daniel Naeff, Ezinwanne Ozoani, Andrew Paverd, Florian Tramèr, and Václav Volhejn.

I’m so excited to see papers like this starting to appear. I wrote about Google DeepMind’s Defeating Prompt Injections by Design paper (aka the CaMeL paper) back in April, which was the first paper I’d seen that proposed a credible solution to some of the challenges posed by prompt injection against tool-using LLM systems (often referred to as “agents”).

This new paper provides a robust explanation of prompt injection, then proposes six design patterns to help protect against it, including the pattern proposed by the CaMeL paper.

- The scope of the problem

- The Action-Selector Pattern

- The Plan-Then-Execute Pattern

- The LLM Map-Reduce Pattern

- The Dual LLM Pattern

- The Code-Then-Execute Pattern

- The Context-Minimization pattern

- The case studies

- Closing thoughts

The scope of the problem

The authors of this paper very clearly understand the scope of the problem:

As long as both agents and their defenses rely on the current class of language models, we believe it is unlikely that general-purpose agents can provide meaningful and reliable safety guarantees.

This leads to a more productive question: what kinds of agents can we build today that produce useful work while offering resistance to prompt injection attacks? In this section, we introduce a set of design patterns for LLM agents that aim to mitigate — if not entirely eliminate — the risk of prompt injection attacks. These patterns impose intentional constraints on agents, explicitly limiting their ability to perform arbitrary tasks.

This is a very realistic approach. We don’t have a magic solution to prompt injection, so we need to make trade-offs. The trade-off they make here is “limiting the ability of agents to perform arbitrary tasks”. That’s not a popular trade-off, but it gives this paper a lot of credibility in my eye.

This paragraph proves that they fully get it (emphasis mine):

The design patterns we propose share a common guiding principle: once an LLM agent has ingested untrusted input, it must be constrained so that it is impossible for that input to trigger any consequential actions—that is, actions with negative side effects on the system or its environment. At a minimum, this means that restricted agents must not be able to invoke tools that can break the integrity or confidentiality of the system. Furthermore, their outputs should not pose downstream risks — such as exfiltrating sensitive information (e.g., via embedded links) or manipulating future agent behavior (e.g., harmful responses to a user query).

The way I think about this is that any exposure to potentially malicious tokens entirely taints the output for that prompt. Any attacker who can sneak in their tokens should be considered to have complete control over what happens next—which means they control not just the textual output of the LLM but also any tool calls that the LLM might be able to invoke.

Let’s talk about their design patterns.

The Action-Selector Pattern

A relatively simple pattern that makes agents immune to prompt injections — while still allowing them to take external actions — is to prevent any feedback from these actions back into the agent.

Agents can trigger tools, but cannot be exposed to or act on the responses from those tools. You can’t read an email or retrieve a web page, but you can trigger actions such as “send the user to this web page” or “display this message to the user”.

They summarize this pattern as an “LLM-modulated switch statement”, which feels accurate to me.

The Plan-Then-Execute Pattern

A more permissive approach is to allow feedback from tool outputs back to the agent, but to prevent the tool outputs from influencing the choice of actions taken by the agent.

The idea here is to plan the tool calls in advance before any chance of exposure to untrusted content. This allows for more sophisticated sequences of actions, without the risk that one of those actions might introduce malicious instructions that then trigger unplanned harmful actions later on.

Their example converts “send today’s schedule to my boss John Doe” into a calendar.read() tool call followed by an email.write(..., 'john.doe@company.com'). The calendar.read() output might be able to corrupt the body of the email that is sent, but it won’t be able to change the recipient of that email.

The LLM Map-Reduce Pattern

The previous pattern still enabled malicious instructions to affect the content sent to the next step. The Map-Reduce pattern involves sub-agents that are directed by the co-ordinator, exposed to untrusted content and have their results safely aggregated later on.

In their example an agent is asked to find files containing this month’s invoices and send them to the accounting department. Each file is processed by a sub-agent that responds with a boolean indicating whether the file is relevant or not. Files that were judged relevant are then aggregated and sent.

They call this the map-reduce pattern because it reflects the classic map-reduce framework for distributed computation.

The Dual LLM Pattern

I get a citation here! I described the The Dual LLM pattern for building AI assistants that can resist prompt injection back in April 2023, and it influenced the CaMeL paper as well.

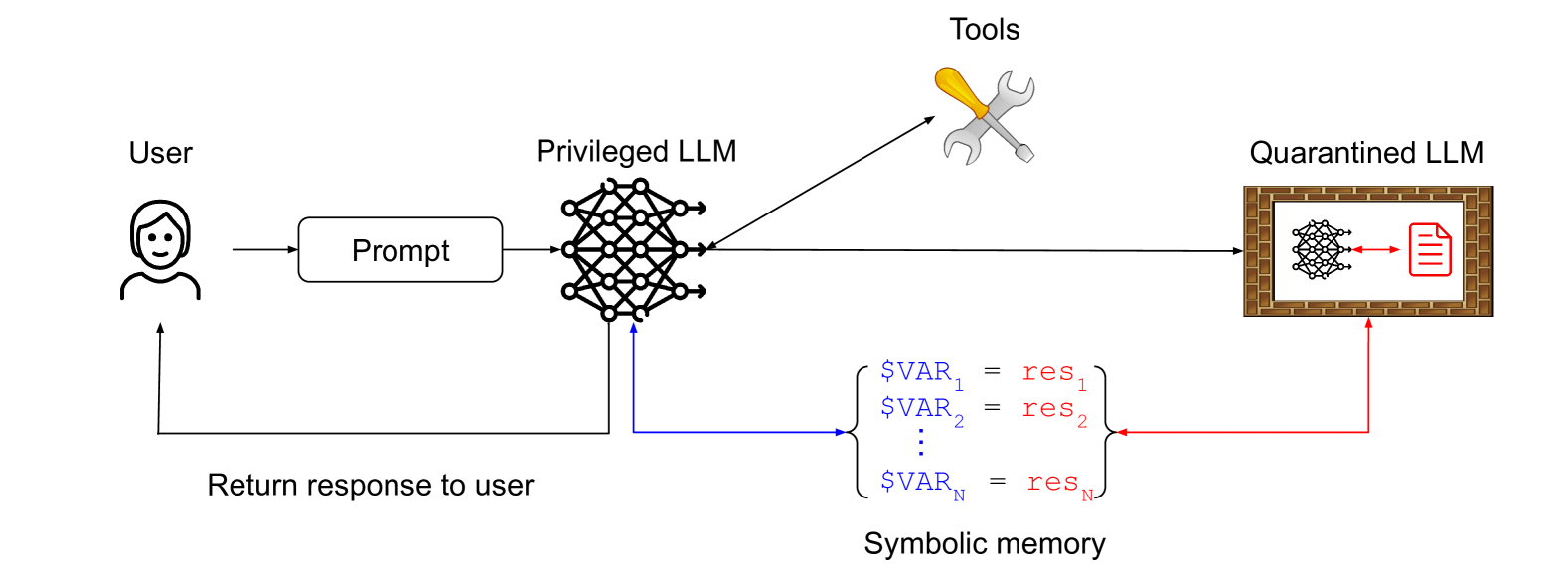

They describe my exact pattern, and even illustrate it with this diagram:

The key idea here is that a privileged LLM co-ordinates a quarantined LLM, avoiding any exposure to untrusted content. The quarantined LLM returns symbolic variables—$VAR1 representing a summarized web page for example—which the privileged LLM can request are shown to the user without being exposed to that tainted content itself.

The Code-Then-Execute Pattern

This is the pattern described by DeepMind’s CaMeL paper. It’s an improved version of my dual LLM pattern, where the privileged LLM generates code in a custom sandboxed DSL that specifies which tools should be called and how their outputs should be passed to each other.

The DSL is designed to enable full data flow analysis, such that any tainted data can be marked as such and tracked through the entire process.

The Context-Minimization pattern

To prevent certain user prompt injections, the agent system can remove unnecessary content from the context over multiple interactions.

For example, suppose that a malicious user asks a customer service chatbot for a quote on a new car and tries to prompt inject the agent to give a large discount. The system could ensure that the agent first translates the user’s request into a database query (e.g., to find the latest offers). Then, before returning the results to the customer, the user’s prompt is removed from the context, thereby preventing the prompt injection.

I’m slightly confused by this one, but I think I understand what it’s saying. If a user’s prompt is converted into a SQL query which returns raw data from a database, and that data is returned in a way that cannot possibly include any of the text from the original prompt, any chance of a prompt injection sneaking through should be eliminated.

The case studies

The rest of the paper presents ten case studies to illustrate how thes design patterns can be applied in practice, each accompanied by detailed threat models and potential mitigation strategies.

Most of these are extremely practical and detailed. The SQL Agent case study, for example, involves an LLM with tools for accessing SQL databases and writing and executing Python code to help with the analysis of that data. This is a highly challenging environment for prompt injection, and the paper spends three pages exploring patterns for building this in a responsible way.

Here’s the full list of case studies. It’s worth spending time with any that correspond to work that you are doing:

- OS Assistant

- SQL Agent

- Email & Calendar Assistant

- Customer Service Chatbot

- Booking Assistant

- Product Recommender

- Resume Screening Assistant

- Medication Leaflet Chatbot

- Medical Diagnosis Chatbot

- Software Engineering Agent

Here’s an interesting suggestion from that last Software Engineering Agent case study on how to safely consume API information from untrusted external documentation:

The safest design we can consider here is one where the code agent only interacts with untrusted documentation or code by means of a strictly formatted interface (e.g., instead of seeing arbitrary code or documentation, the agent only sees a formal API description). This can be achieved by processing untrusted data with a quarantined LLM that is instructed to convert the data into an API description with strict formatting requirements to minimize the risk of prompt injections (e.g., method names limited to 30 characters).

- Utility: Utility is reduced because the agent can only see APIs and no natural language descriptions or examples of third-party code.

- Security: Prompt injections would have to survive being formatted into an API description, which is unlikely if the formatting requirements are strict enough.

I wonder if it is indeed safe to allow up to 30 character method names... it could be that a truly creative attacker could come up with a method name like run_rm_dash_rf_for_compliance() that causes havoc even given those constraints.

Closing thoughts

I’ve been writing about prompt injection for nearly three years now, but I’ve never had the patience to try and produce a formal paper on the subject. It’s a huge relief to see papers of this quality start to emerge.

Prompt injection remains the biggest challenge to responsibly deploying the kind of agentic systems everyone is so excited to build. The more attention this family of problems gets from the research community the better.

More recent articles

- Two new Showboat tools: Chartroom and datasette-showboat - 17th February 2026

- Deep Blue - 15th February 2026

- The evolution of OpenAI's mission statement - 13th February 2026