Sunday, 13th October 2024

PostgreSQL 17: SQL/JSON is here! (via) Hubert Lubaczewski dives into the new JSON features added in PostgreSQL 17, released a few weeks ago on the 26th of September. This is the latest in his long series of similar posts about new PostgreSQL features.

The features are based on the new SQL:2023 standard from June 2023. If you want to actually read the specification for SQL:2023 it looks like you have to buy a PDF from ISO for 194 Swiss Francs (currently $226). Here's a handy summary by Peter Eisentraut: SQL:2023 is finished: Here is what's new.

There's a lot of neat stuff in here. I'm particularly interested in the json_table() table-valued function, which can convert a JSON string into a table with quite a lot of flexibility. You can even specify a full table schema as part of the function call:

SELECT * FROM json_table(

'[{"a":10,"b":20},{"a":30,"b":40}]'::jsonb,

'$[*]'

COLUMNS (

id FOR ORDINALITY,

column_a int4 path '$.a',

column_b int4 path '$.b',

a int4,

b int4,

c text

)

);SQLite has solid JSON support already and often imitates PostgreSQL features, so I wonder if we'll see an update to SQLite that reflects some aspects of this new syntax.

An LLM TDD loop (via) Super neat demo by David Winterbottom, who wrapped my LLM and files-to-prompt tools in a short Bash script that can be fed a file full of Python unit tests and an empty implementation file and will then iterate on that file in a loop until the tests pass.

Zero-latency SQLite storage in every Durable Object (via) Kenton Varda introduces the next iteration of Cloudflare's Durable Object platform, which recently upgraded from a key/value store to a full relational system based on SQLite.

For useful background on the first version of Durable Objects take a look at Cloudflare's durable multiplayer moat by Paul Butler, who digs into its popularity for building WebSocket-based realtime collaborative applications.

The new SQLite-backed Durable Objects is a fascinating piece of distributed system design, which advocates for a really interesting way to architect a large scale application.

The key idea behind Durable Objects is to colocate application logic with the data it operates on. A Durable Object comprises code that executes on the same physical host as the SQLite database that it uses, resulting in blazingly fast read and write performance.

How could this work at scale?

A single object is inherently limited in throughput since it runs on a single thread of a single machine. To handle more traffic, you create more objects. This is easiest when different objects can handle different logical units of state (like different documents, different users, or different "shards" of a database), where each unit of state has low enough traffic to be handled by a single object

Kenton presents the example of a flight booking system, where each flight can map to a dedicated Durable Object with its own SQLite database - thousands of fresh databases per airline per day.

Each DO has a unique name, and Cloudflare's network then handles routing requests to that object wherever it might live on their global network.

The technical details are fascinating. Inspired by Litestream, each DO constantly streams a sequence of WAL entries to object storage - batched every 16MB or every ten seconds. This also enables point-in-time recovery for up to 30 days through replaying those logged transactions.

To ensure durability within that ten second window, writes are also forwarded to five replicas in separate nearby data centers as soon as they commit, and the write is only acknowledged once three of them have confirmed it.

The JavaScript API design is interesting too: it's blocking rather than async, because the whole point of the design is to provide fast single threaded persistence operations:

let docs = sql.exec(`

SELECT title, authorId FROM documents

ORDER BY lastModified DESC

LIMIT 100

`).toArray();

for (let doc of docs) {

doc.authorName = sql.exec(

"SELECT name FROM users WHERE id = ?",

doc.authorId).one().name;

}This one of their examples deliberately exhibits the N+1 query pattern, because that's something SQLite is uniquely well suited to handling.

The system underlying Durable Objects is called Storage Relay Service, and it's been powering Cloudflare's existing-but-different D1 SQLite system for over a year.

I was curious as to where the objects are created. According to this (via Hacker News):

Durable Objects do not currently change locations after they are created. By default, a Durable Object is instantiated in a data center close to where the initial

get()request is made. [...] To manually create Durable Objects in another location, provide an optionallocationHintparameter toget().

And in a footnote:

Dynamic relocation of existing Durable Objects is planned for the future.

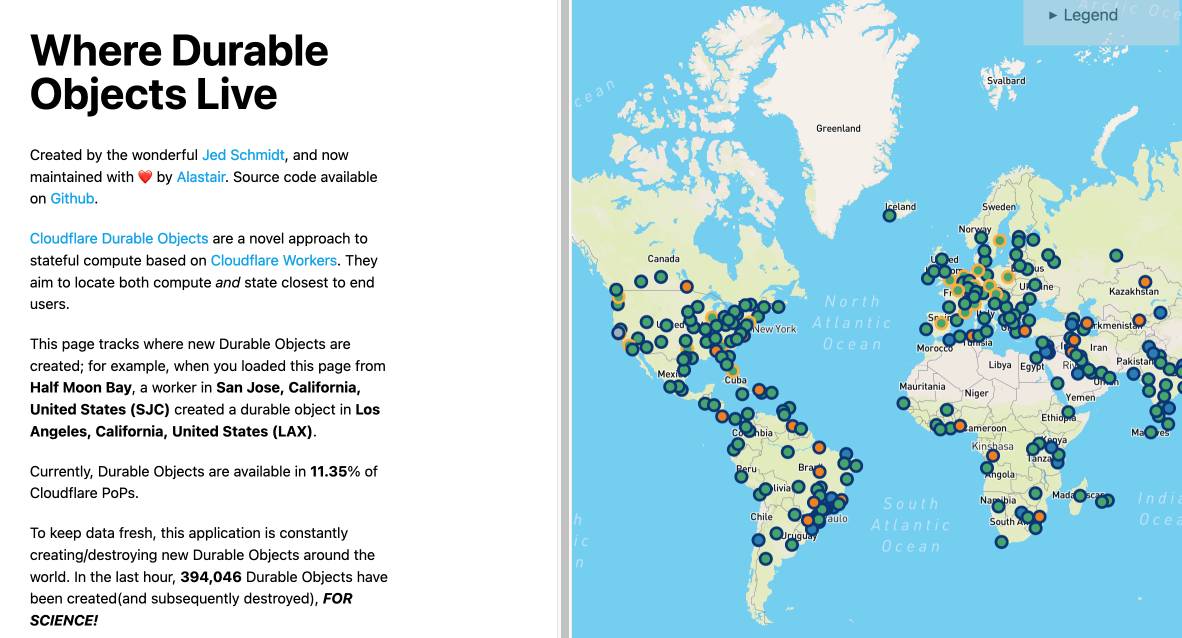

where.durableobjects.live is a neat site that tracks where in the Cloudflare network DOs are created - I just visited it and it said:

This page tracks where new Durable Objects are created; for example, when you loaded this page from Half Moon Bay, a worker in San Jose, California, United States (SJC) created a durable object in San Jose, California, United States (SJC).