Wilson Lin on FastRender: a browser built by thousands of parallel agents

23rd January 2026

Last week Cursor published Scaling long-running autonomous coding, an article describing their research efforts into coordinating large numbers of autonomous coding agents. One of the projects mentioned in the article was FastRender, a web browser they built from scratch using their agent swarms. I wanted to learn more so I asked Wilson Lin, the engineer behind FastRender, if we could record a conversation about the project. That 47 minute video is now available on YouTube. I’ve included some of the highlights below.

See my previous post for my notes and screenshots from trying out FastRender myself.

What FastRender can do right now

We started the conversation with a demo of FastRender loading different pages (03:15). The JavaScript engine isn’t working yet so we instead loaded github.com/wilsonzlin/fastrender, Wikipedia and CNN—all of which were usable, if a little slow to display.

JavaScript had been disabled by one of the agents, which decided to add a feature flag! 04:02

JavaScript is disabled right now. The agents made a decision as they were currently still implementing the engine and making progress towards other parts... they decided to turn it off or put it behind a feature flag, technically.

From side-project to core research

Wilson started what become FastRender as a personal side-project to explore the capabilities of the latest generation of frontier models—Claude Opus 4.5, GPT-5.1, and GPT-5.2. 00:56

FastRender was a personal project of mine from, I’d say, November. It was an experiment to see how well frontier models like Opus 4.5 and back then GPT-5.1 could do with much more complex, difficult tasks.

A browser rendering engine was the ideal choice for this, because it’s both extremely ambitious and complex but also well specified. And you can visually see how well it’s working! 01:57

As that experiment progressed, I was seeing better and better results from single agents that were able to actually make good progress on this project. And at that point, I wanted to see, well, what’s the next level? How do I push this even further?

Once it became clear that this was an opportunity to try multiple agents working together it graduated to an official Cursor research project, and available resources were amplified.

The goal of FastRender was never to build a browser to compete with the likes of Chrome. 41:52

We never intended for it to be a production software or usable, but we wanted to observe behaviors of this harness of multiple agents, to see how they could work at scale.

The great thing about a browser is that it has such a large scope that it can keep serving experiments in this space for many years to come. JavaScript, then WebAssembly, then WebGPU... it could take many years to run out of new challenges for the agents to tackle.

Running thousands of agents at once

The most interesting thing about FastRender is the way the project used multiple agents working in parallel to build different parts of the browser. I asked how many agents were running at once: 05:24

At the peak, when we had the stable system running for one week continuously, there were approximately 2,000 agents running concurrently at one time. And they were making, I believe, thousands of commits per hour.

The project has nearly 30,000 commits!

How do you run 2,000 agents at once? They used really big machines. 05:56

The simple approach we took with the infrastructure was to have a large machine run one of these multi-agent harnesses. Each machine had ample resources, and it would run about 300 agents concurrently on each. This was able to scale and run reasonably well, as agents spend a lot of time thinking, and not just running tools.

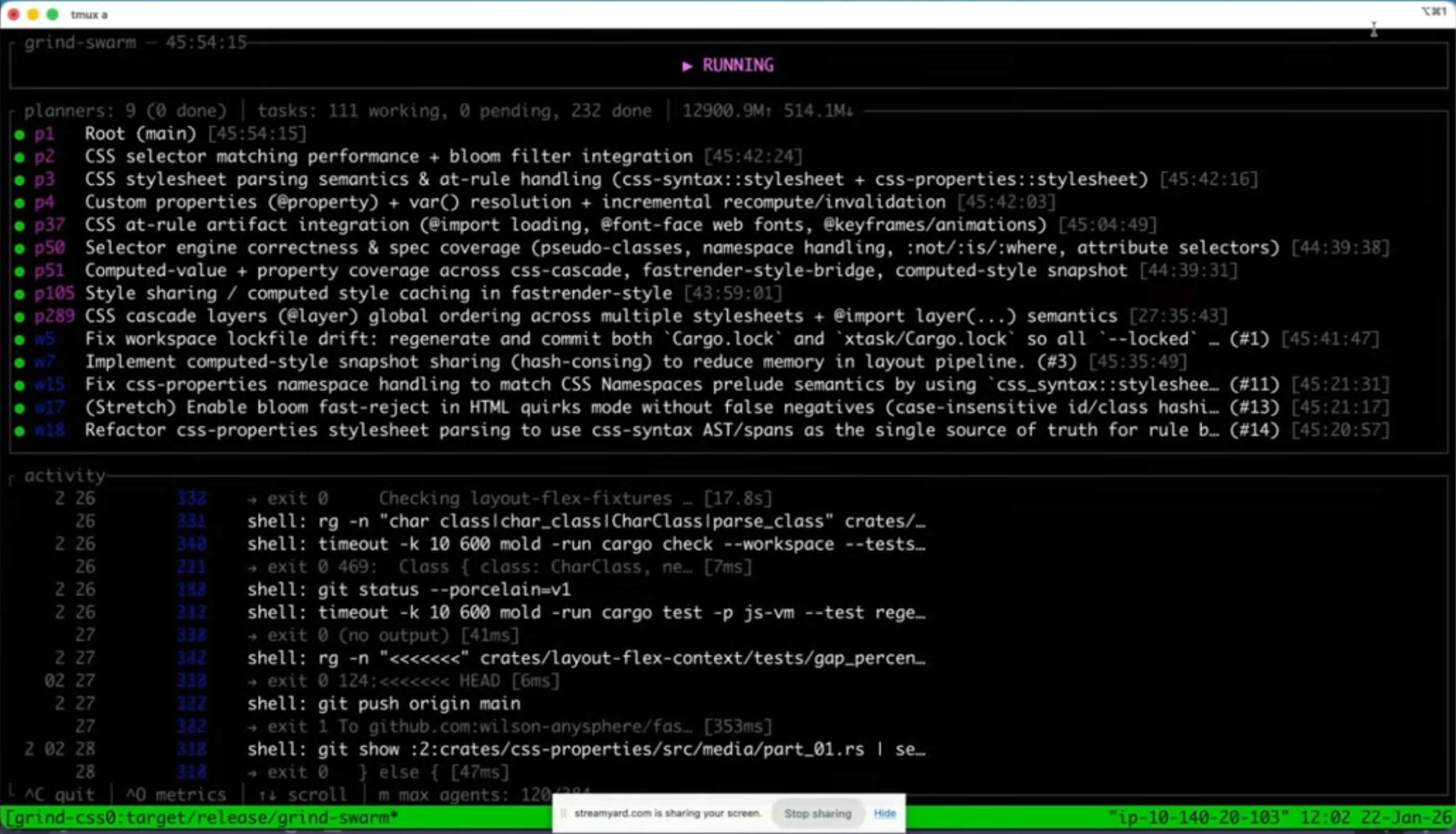

At this point we switched to a live demo of the harness running on one of those big machines (06:32). The agents are arranged in a tree structure, with planning agents firing up tasks and worker agents then carrying them out. 07:14

This cluster of agents is working towards building out the CSS aspects of the browser, whether that’s parsing, selector engine, those features. We managed to push this even further by splitting out the browser project into multiple instructions or work streams and have each one run one of these harnesses on their own machine, so that was able to further parallelize and increase throughput.

But don’t all of these agents working on the same codebase result in a huge amount of merge conflicts? Apparently not: 08:21

We’ve noticed that most commits do not have merge conflicts. The reason is the harness itself is able to quite effectively split out and divide the scope and tasks such that it tries to minimize the amount of overlap of work. That’s also reflected in the code structure—commits will be made at various times and they don’t tend to touch each other at the same time.

This appears to be the key trick for unlocking benefits from parallel agents: if planning agents do a good enough job of breaking up the work into non-overlapping chunks you can bring hundreds or even thousands of agents to bear on a problem at once.

Surprisingly, Wilson found that GPT-5.1 and GPT-5.2 were a better fit for this work than the coding specialist GPT-5.1-Codex: 17:28

Some initial findings were that the instructions here were more expansive than merely coding. For example, how to operate and interact within a harness, or how to operate autonomously without interacting with the user or having a lot of user feedback. These kinds of instructions we found worked better with the general models.

I asked what the longest they’ve seen this system run without human intervention: 18:28

So this system, once you give an instruction, there’s actually no way to steer it, you can’t prompt it, you’re going to adjust how it goes. The only thing you can do is stop it. So our longest run, all the runs are basically autonomous. We don’t alter the trajectory while executing. [...]

And so the longest at the time of the post was about a week and that’s pretty close to the longest. Of course the research project itself was only about three weeks so you know we probably can go longer.

Specifications and feedback loops

An interesting aspect of this project design is feedback loops. For agents to work autonomously for long periods of time they need as much useful context about the problem they are solving as possible, combined with effective feedback loops to help them make decisions.

The FastRender repo uses git submodules to include relevant specifications, including csswg-drafts, tc39-ecma262 for JavaScript, whatwg-dom, whatwg-html and more. 14:06

Feedback loops to the system are very important. Agents are working for very long periods continuously, and without guardrails and feedback to know whether what they’re doing is right or wrong it can have a big impact over a long rollout. Specs are definitely an important part—you can see lots of comments in the code base that AI wrote referring specifically to specs that they found in the specs submodules.

GPT-5.2 is a vision-capable model, and part of the feedback loop for FastRender included taking screenshots of the rendering results and feeding those back into the model: 16:23

In the earlier evolution of this project, when it was just doing the static renderings of screenshots, this was definitely a very explicit thing we taught it to do. And these models are visual models, so they do have that ability. We have progress indicators to tell it to compare the diff against a golden sample.

The strictness of the Rust compiler helped provide a feedback loop as well: 15:52

The nice thing about Rust is you can get a lot of verification just from compilation, and that is not as available in other languages.

The agents chose the dependencies

We talked about the Cargo.toml dependencies that the project had accumulated, almost all of which had been selected by the agents themselves.

Some of these, like Skia for 2D graphics rendering or HarfBuzz for text shaping, were obvious choices. Others such as Taffy felt like they might go against the from-scratch goals of the project, since that library implements CSS flexbox and grid layout algorithms directly. This was not an intended outcome. 27:53

Similarly these are dependencies that the agent picked to use for small parts of the engine and perhaps should have actually implemented itself. I think this reflects on the importance of the instructions, because I actually never encoded specifically the level of dependencies we should be implementing ourselves.

The agents vendored in Taffy and applied a stream of changes to that vendored copy. 31:18

It’s currently vendored. And as the agents work on it, they do make changes to it. This was actually an artifact from the very early days of the project before it was a fully fledged browser... it’s implementing things like the flex and grid layers, but there are other layout methods like inline, block, and table, and in our new experiment, we’re removing that completely.

The inclusion of QuickJS despite the presence of a home-grown ecma-rs implementation has a fun origin story: 35:15

I believe it mentioned that it pulled in the QuickJS because it knew that other agents were working on the JavaScript engine, and it needed to unblock itself quickly. [...]

It was like, eventually, once that’s finished, let’s remove it and replace with the proper engine.

I love how similar this is to the dynamics of a large-scale human engineering team, where you could absolutely see one engineer getting frustrated at another team not having delivered yet and unblocking themselves by pulling in a third-party library.

Intermittent errors are OK, actually

Here’s something I found really surprising: the agents were allowed to introduce small errors into the codebase as they worked! 39:42

One of the trade-offs was: if you wanted every single commit to be a hundred percent perfect, make sure it can always compile every time, that might be a synchronization bottleneck. [...]

Especially as you break up the system into more modularized aspects, you can see that errors get introduced, but small errors, right? An API change or some syntax error, but then they get fixed really quickly after a few commits. So there’s a little bit of slack in the system to allow these temporary errors so that the overall system can continue to make progress at a really high throughput. [...]

People may say, well, that’s not correct code. But it’s not that the errors are accumulating. It’s a stable rate of errors. [...] That seems like a worthwhile trade-off.

If you’re going to have thousands of agents working in parallel optimizing for throughput over correctness turns out to be a strategy worth exploring.

A single engineer plus a swarm of agents in January 2026

The thing I find most interesting about FastRender is how it demonstrates the extreme edge of what a single engineer can achieve in early 2026 with the assistance of a swarm of agents.

FastRender may not be a production-ready browser, but it represents over a million lines of Rust code, written in a few weeks, that can already render real web pages to a usable degree.

A browser really is the ideal research project to experiment with this new, weirdly shaped form of software engineering.

I asked Wilson how much mental effort he had invested in browser rendering compared to agent co-ordination. 11:34

The browser and this project were co-developed and very symbiotic, only because the browser was a very useful objective for us to measure and iterate the progress of the harness. The goal was to iterate on and research the multi-agent harness—the browser was just the research example or objective.

FastRender is effectively using a full browser rendering engine as a “hello world” exercise for multi-agent coordination!

More recent articles

- Can coding agents relicense open source through a “clean room” implementation of code? - 5th March 2026

- Something is afoot in the land of Qwen - 4th March 2026

- I vibe coded my dream macOS presentation app - 25th February 2026