GPT-5: Key characteristics, pricing and model card

7th August 2025

I’ve had preview access to the new GPT-5 model family for the past two weeks (see related video and my disclosures) and have been using GPT-5 as my daily-driver. It’s my new favorite model. It’s still an LLM—it’s not a dramatic departure from what we’ve had before—but it rarely screws up and generally feels competent or occasionally impressive at the kinds of things I like to use models for.

I’ve collected a lot of notes over the past two weeks, so I’ve decided to break them up into a series of posts. This first one will cover key characteristics of the models, how they are priced and what we can learn from the GPT-5 system card.

- Key model characteristics

- Position in the OpenAI model family

- Pricing is aggressively competitive

- More notes from the system card

- Prompt injection in the system card

- Thinking traces in the API

- And some SVGs of pelicans

Key model characteristics

Let’s start with the fundamentals. GPT-5 in ChatGPT is a weird hybrid that switches between different models. Here’s what the system card says about that (my highlights in bold):

GPT-5 is a unified system with a smart and fast model that answers most questions, a deeper reasoning model for harder problems, and a real-time router that quickly decides which model to use based on conversation type, complexity, tool needs, and explicit intent (for example, if you say “think hard about this” in the prompt). [...] Once usage limits are reached, a mini version of each model handles remaining queries. In the near future, we plan to integrate these capabilities into a single model.

GPT-5 in the API is simpler: it’s available as three models—regular, mini and nano—which can each be run at one of four reasoning levels: minimal (a new level not previously available for other OpenAI reasoning models), low, medium or high.

The models have an input limit of 272,000 tokens and an output limit (which includes invisible reasoning tokens) of 128,000 tokens. They support text and image for input, text only for output.

I’ve mainly explored full GPT-5. My verdict: it’s just good at stuff. It doesn’t feel like a dramatic leap ahead from other LLMs but it exudes competence—it rarely messes up, and frequently impresses me. I’ve found it to be a very sensible default for everything that I want to do. At no point have I found myself wanting to re-run a prompt against a different model to try and get a better result.

Here are the OpenAI model pages for GPT-5, GPT-5 mini and GPT-5 nano. Knowledge cut-off is September 30th 2024 for GPT-5 and May 30th 2024 for GPT-5 mini and nano.

Position in the OpenAI model family

The three new GPT-5 models are clearly intended as a replacement for most of the rest of the OpenAI line-up. This table from the system card is useful, as it shows how they see the new models fitting in:

| Previous model | GPT-5 model |

|---|---|

| GPT-4o | gpt-5-main |

| GPT-4o-mini | gpt-5-main-mini |

| OpenAI o3 | gpt-5-thinking |

| OpenAI o4-mini | gpt-5-thinking-mini |

| GPT-4.1-nano | gpt-5-thinking-nano |

| OpenAI o3 Pro | gpt-5-thinking-pro |

That “thinking-pro” model is currently only available via ChatGPT where it is labelled as “GPT-5 Pro” and limited to the $200/month tier. It uses “parallel test time compute”.

The only capabilities not covered by GPT-5 are audio input/output and image generation. Those remain covered by models like GPT-4o Audio and GPT-4o Realtime and their mini variants and the GPT Image 1 and DALL-E image generation models.

Pricing is aggressively competitive

The pricing is aggressively competitive with other providers.

- GPT-5: $1.25/million for input, $10/million for output

- GPT-5 Mini: $0.25/m input, $2.00/m output

- GPT-5 Nano: $0.05/m input, $0.40/m output

GPT-5 is priced at half the input cost of GPT-4o, and maintains the same price for output. Those invisible reasoning tokens count as output tokens so you can expect most prompts to use more output tokens than their GPT-4o equivalent (unless you set reasoning effort to “minimal”).

The discount for token caching is significant too: 90% off on input tokens that have been used within the previous few minutes. This is particularly material if you are implementing a chat UI where the same conversation gets replayed every time the user adds another prompt to the sequence.

Here’s a comparison table I put together showing the new models alongside the most comparable models from OpenAI’s competition:

| Model | Input $/m | Output $/m |

|---|---|---|

| Claude Opus 4.1 | 15.00 | 75.00 |

| Claude Sonnet 4 | 3.00 | 15.00 |

| Grok 4 | 3.00 | 15.00 |

| Gemini 2.5 Pro (>200,000) | 2.50 | 15.00 |

| GPT-4o | 2.50 | 10.00 |

| GPT-4.1 | 2.00 | 8.00 |

| o3 | 2.00 | 8.00 |

| Gemini 2.5 Pro (<200,000) | 1.25 | 10.00 |

| GPT-5 | 1.25 | 10.00 |

| o4-mini | 1.10 | 4.40 |

| Claude 3.5 Haiku | 0.80 | 4.00 |

| GPT-4.1 mini | 0.40 | 1.60 |

| Gemini 2.5 Flash | 0.30 | 2.50 |

| Grok 3 Mini | 0.30 | 0.50 |

| GPT-5 Mini | 0.25 | 2.00 |

| GPT-4o mini | 0.15 | 0.60 |

| Gemini 2.5 Flash-Lite | 0.10 | 0.40 |

| GPT-4.1 Nano | 0.10 | 0.40 |

| Amazon Nova Lite | 0.06 | 0.24 |

| GPT-5 Nano | 0.05 | 0.40 |

| Amazon Nova Micro | 0.035 | 0.14 |

(Here’s a good example of a GPT-5 failure: I tried to get it to output that table sorted itself but it put Nova Micro as more expensive than GPT-5 Nano, so I prompted it to “construct the table in Python and sort it there” and that fixed the issue.)

More notes from the system card

As usual, the system card is vague on what went into the training data. Here’s what it says:

Like OpenAI’s other models, the GPT-5 models were trained on diverse datasets, including information that is publicly available on the internet, information that we partner with third parties to access, and information that our users or human trainers and researchers provide or generate. [...] We use advanced data filtering processes to reduce personal information from training data.

I found this section interesting, as it reveals that writing, code and health are three of the most common use-cases for ChatGPT. This explains why so much effort went into health-related questions, for both GPT-5 and the recently released OpenAI open weight models.

We’ve made significant advances in reducing hallucinations, improving instruction following, and minimizing sycophancy, and have leveled up GPT-5’s performance in three of ChatGPT’s most common uses: writing, coding, and health. All of the GPT-5 models additionally feature safe-completions, our latest approach to safety training to prevent disallowed content.

Safe-completions is later described like this:

Large language models such as those powering ChatGPT have traditionally been trained to either be as helpful as possible or outright refuse a user request, depending on whether the prompt is allowed by safety policy. [...] Binary refusal boundaries are especially ill-suited for dual-use cases (such as biology or cybersecurity), where a user request can be completed safely at a high level, but may lead to malicious uplift if sufficiently detailed or actionable. As an alternative, we introduced safe- completions: a safety-training approach that centers on the safety of the assistant’s output rather than a binary classification of the user’s intent. Safe-completions seek to maximize helpfulness subject to the safety policy’s constraints.

So instead of straight up refusals, we should expect GPT-5 to still provide an answer but moderate that answer to avoid it including “harmful” content.

OpenAI have a paper about this which I haven’t read yet (I didn’t get early access): From Hard Refusals to Safe-Completions: Toward Output-Centric Safety Training.

Sycophancy gets a mention, unsurprising given their high profile disaster in April. They’ve worked on this in the core model:

System prompts, while easy to modify, have a more limited impact on model outputs relative to changes in post-training. For GPT-5, we post-trained our models to reduce sycophancy. Using conversations representative of production data, we evaluated model responses, then assigned a score reflecting the level of sycophancy, which was used as a reward signal in training.

They claim impressive reductions in hallucinations. In my own usage I’ve not spotted a single hallucination yet, but that’s been true for me for Claude 4 and o3 recently as well—hallucination is so much less of a problem with this year’s models.

Update: I have had some reasonable pushback against this point, so I should clarify what I mean here. When I use the term “hallucination” I am talking about instances where the model confidently states a real-world fact that is untrue—like the incorrect winner of a sporting event. I’m not talking about the models making other kinds of mistakes—they make mistakes all the time!

Someone pointed out that it’s likely I’m avoiding hallucinations through the way I use the models, and this is entirely correct: as an experienced LLM user I instinctively stay clear of prompts that are likely to trigger hallucinations, like asking a non-search-enabled model for URLs or paper citations. This means I’m much less likely to encounter hallucinations in my daily usage.

One of our focuses when training the GPT-5 models was to reduce the frequency of factual hallucinations. While ChatGPT has browsing enabled by default, many API queries do not use browsing tools. Thus, we focused both on training our models to browse effectively for up-to-date information, and on reducing hallucinations when the models are relying on their own internal knowledge.

The section about deception also incorporates the thing where models sometimes pretend they’ve completed a task that defeated them:

We placed gpt-5-thinking in a variety of tasks that were partly or entirely infeasible to accomplish, and rewarded the model for honestly admitting it can not complete the task. [...]

In tasks where the agent is required to use tools, such as a web browsing tool, in order to answer a user’s query, previous models would hallucinate information when the tool was unreliable. We simulate this scenario by purposefully disabling the tools or by making them return error codes.

Prompt injection in the system card

There’s a section about prompt injection, but it’s pretty weak sauce in my opinion.

Two external red-teaming groups conducted a two-week prompt-injection assessment targeting system-level vulnerabilities across ChatGPT’s connectors and mitigations, rather than model-only behavior.

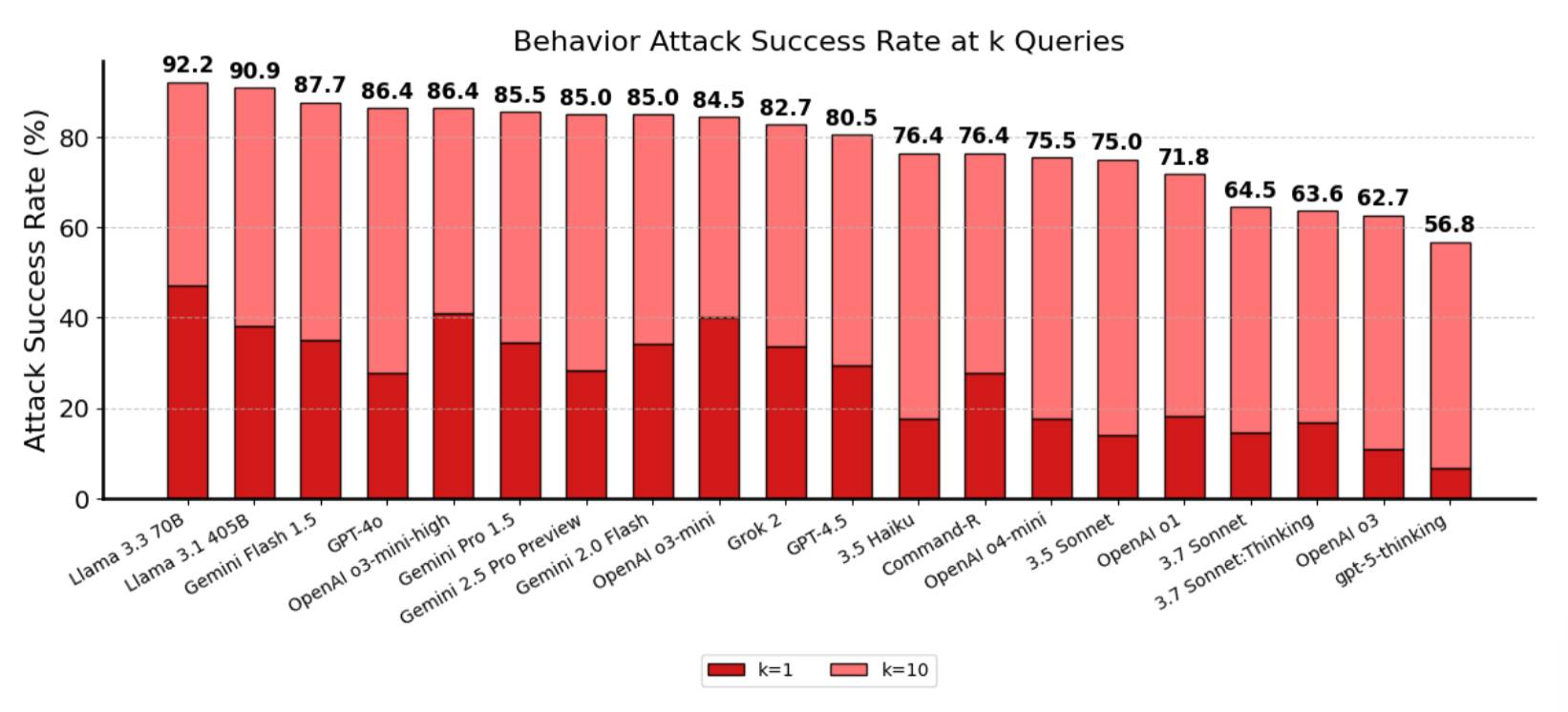

Here’s their chart showing how well the model scores against the rest of the field. It’s an impressive result in comparison—56.8 attack success rate for gpt-5-thinking, where Claude 3.7 scores in the 60s (no Claude 4 results included here) and everything else is 70% plus:

On the one hand, a 56.8% attack rate is cleanly a big improvement against all of those other models.

But it’s also a strong signal that prompt injection continues to be an unsolved problem! That means that more than half of those k=10 attacks (where the attacker was able to try up to ten times) got through.

Don’t assume prompt injection isn’t going to be a problem for your application just because the models got better.

Thinking traces in the API

I had initially thought that my biggest disappointment with GPT-5 was that there’s no way to get at those thinking traces via the API... but that turned out not to be true. The following curl command demonstrates that the responses API "reasoning": {"summary": "auto"} is available for the new GPT-5 models:

curl https://api.openai.com/v1/responses \

-H "Authorization: Bearer $(llm keys get openai)" \

-H "Content-Type: application/json" \

-d '{

"model": "gpt-5",

"input": "Give me a one-sentence fun fact about octopuses.",

"reasoning": {"summary": "auto"}

}'Here’s the response from that API call.

Without that option the API will often provide a lengthy delay while the model burns through thinking tokens until you start getting back visible tokens for the final response.

OpenAI offer a new reasoning_effort=minimal option which turns off most reasoning so that tokens start to stream back to you as quickly as possible.

And some SVGs of pelicans

Naturally I’ve been running my “Generate an SVG of a pelican riding a bicycle” benchmark. I’ll actually spend more time on this in a future post—I have some fun variants I’ve been exploring—but for the moment here’s the pelican I got from GPT-5 running at its default “medium” reasoning effort:

It’s pretty great! Definitely recognizable as a pelican, and one of the best bicycles I’ve seen yet.

Here’s GPT-5 mini:

And GPT-5 nano:

More recent articles

- I vibe coded my dream macOS presentation app - 25th February 2026

- Writing about Agentic Engineering Patterns - 23rd February 2026

- Adding TILs, releases, museums, tools and research to my blog - 20th February 2026