Useful patterns for building HTML tools

10th December 2025

I’ve started using the term HTML tools to refer to HTML applications that I’ve been building which combine HTML, JavaScript, and CSS in a single file and use them to provide useful functionality. I have built over 150 of these in the past two years, almost all of them written by LLMs. This article presents a collection of useful patterns I’ve discovered along the way.

First, some examples to show the kind of thing I’m talking about:

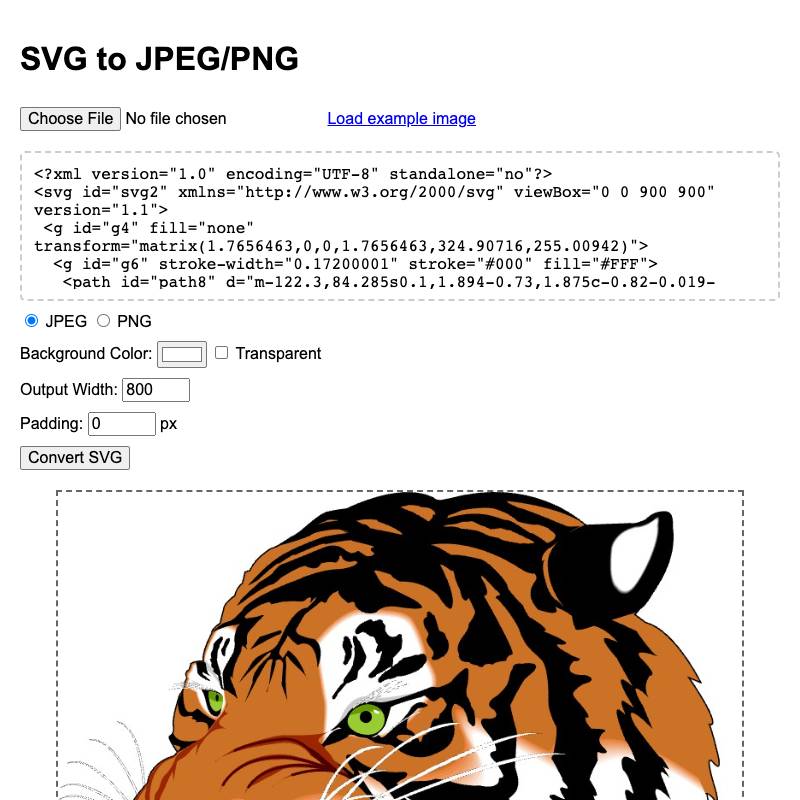

- svg-render renders SVG code to downloadable JPEGs or PNGs

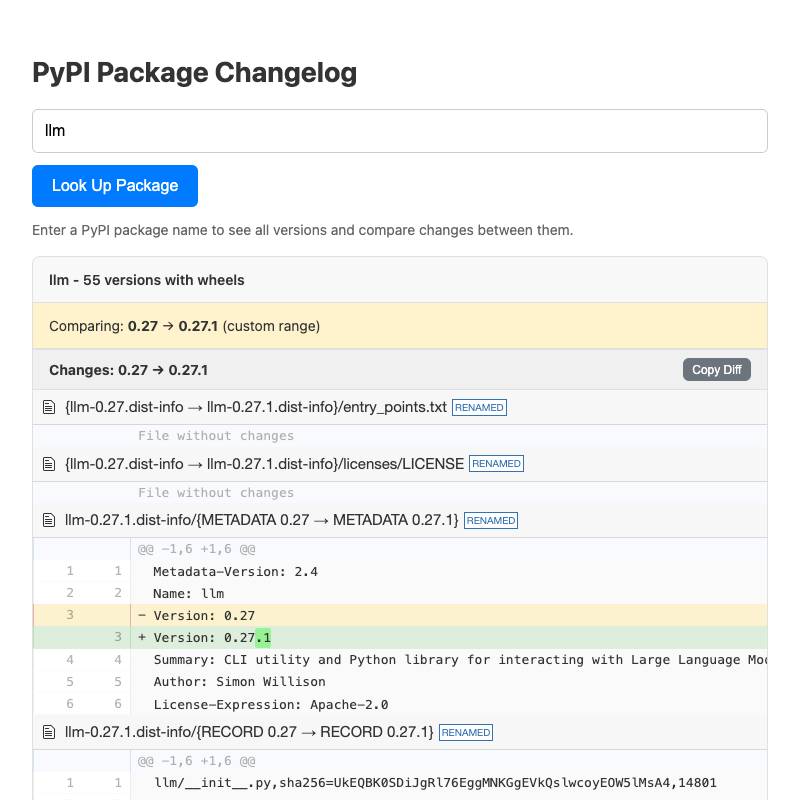

- pypi-changelog lets you generate (and copy to clipboard) diffs between different PyPI package releases.

- bluesky-thread provides a nested view of a discussion thread on Bluesky.

These are some of my recent favorites. I have dozens more like this that I use on a regular basis.

You can explore my collection on tools.simonwillison.net—the by month view is useful for browsing the entire collection.

If you want to see the code and prompts, almost all of the examples in this post include a link in their footer to “view source” on GitHub. The GitHub commits usually contain either the prompt itself or a link to the transcript used to create the tool.

- The anatomy of an HTML tool

- Prototype with Artifacts or Canvas

- Switch to a coding agent for more complex projects

- Load dependencies from CDNs

- Host them somewhere else

- Take advantage of copy and paste

- Build debugging tools

- Persist state in the URL

- Use localStorage for secrets or larger state

- Collect CORS-enabled APIs

- LLMs can be called directly via CORS

- Don’t be afraid of opening files

- You can offer downloadable files too

- Pyodide can run Python code in the browser

- WebAssembly opens more possibilities

- Remix your previous tools

- Record the prompt and transcript

- Go forth and build

The anatomy of an HTML tool

These are the characteristics I have found to be most productive in building tools of this nature:

- A single file: inline JavaScript and CSS in a single HTML file means the least hassle in hosting or distributing them, and crucially means you can copy and paste them out of an LLM response.

- Avoid React, or anything with a build step. The problem with React is that JSX requires a build step, which makes everything massively less convenient. I prompt “no react” and skip that whole rabbit hole entirely.

- Load dependencies from a CDN. The fewer dependencies the better, but if there’s a well known library that helps solve a problem I’m happy to load it from CDNjs or jsdelivr or similar.

- Keep them small. A few hundred lines means the maintainability of the code doesn’t matter too much: any good LLM can read them and understand what they’re doing, and rewriting them from scratch with help from an LLM takes just a few minutes.

The end result is a few hundred lines of code that can be cleanly copied and pasted into a GitHub repository.

Prototype with Artifacts or Canvas

The easiest way to build one of these tools is to start in ChatGPT or Claude or Gemini. All three have features where they can write a simple HTML+JavaScript application and show it to you directly.

Claude calls this “Artifacts”, ChatGPT and Gemini both call it “Canvas”. Claude has the feature enabled by default, ChatGPT and Gemini may require you to toggle it on in their “tools” menus.

Try this prompt in Gemini or ChatGPT:

Build a canvas that lets me paste in JSON and converts it to YAML. No React.

Or this prompt in Claude:

Build an artifact that lets me paste in JSON and converts it to YAML. No React.

I always add “No React” to these prompts, because otherwise they tend to build with React, resulting in a file that is harder to copy and paste out of the LLM and use elsewhere. I find that attempts which use React take longer to display (since they need to run a build step) and are more likely to contain crashing bugs for some reason, especially in ChatGPT.

All three tools have “share” links that provide a URL to the finished application. Examples:

- ChatGPT JSON to YAML Canvas made with GPT-5.1 Thinking—here’s the full ChatGPT transcript

- Claude JSON to YAML Artifact made with Claude Opus 4.5—here’s the full Claude transcript

- Gemini JSON to YAML Canvas made with Gemini 3 Pro—here’s the full Gemini transcript

Switch to a coding agent for more complex projects

Coding agents such as Claude Code and Codex CLI have the advantage that they can test the code themselves while they work on it using tools like Playwright. I often upgrade to one of those when I’m working on something more complicated, like my Bluesky thread viewer tool shown above.

I also frequently use asynchronous coding agents like Claude Code for web to make changes to existing tools. I shared a video about that in Building a tool to copy-paste share terminal sessions using Claude Code for web.

Claude Code for web and Codex Cloud run directly against my simonw/tools repo, which means they can publish or upgrade tools via Pull Requests (here are dozens of examples) without me needing to copy and paste anything myself.

Load dependencies from CDNs

Any time I use an additional JavaScript library as part of my tool I like to load it from a CDN.

The three major LLM platforms support specific CDNs as part of their Artifacts or Canvas features, so often if you tell them “Use PDF.js” or similar they’ll be able to compose a URL to a CDN that’s on their allow-list.

Sometimes you’ll need to go and look up the URL on cdnjs or jsDelivr and paste it into the chat.

CDNs like these have been around for long enough that I’ve grown to trust them, especially for URLs that include the package version.

The alternative to CDNs is to use npm and have a build step for your projects. I find this reduces my productivity at hacking on individual tools and makes it harder to self-host them.

Host them somewhere else

I don’t like leaving my HTML tools hosted by the LLM platforms themselves for a couple of reasons. First, LLM platforms tend to run the tools inside a tight sandbox with a lot of restrictions. They’re often unable to load data or images from external URLs, and sometimes even features like linking out to other sites are disabled.

The end-user experience often isn’t great either. They show warning messages to new users, often take additional time to load and delight in showing promotions for the platform that was used to create the tool.

They’re also not as reliable as other forms of static hosting. If ChatGPT or Claude are having an outage I’d like to still be able to access the tools I’ve created in the past.

Being able to easily self-host is the main reason I like insisting on “no React” and using CDNs for dependencies—the absence of a build step makes hosting tools elsewhere a simple case of copying and pasting them out to some other provider.

My preferred provider here is GitHub Pages because I can paste a block of HTML into a file on github.com and have it hosted on a permanent URL a few seconds later. Most of my tools end up in my simonw/tools repository which is configured to serve static files at tools.simonwillison.net.

Take advantage of copy and paste

One of the most useful input/output mechanisms for HTML tools comes in the form of copy and paste.

I frequently build tools that accept pasted content, transform it in some way and let the user copy it back to their clipboard to paste somewhere else.

Copy and paste on mobile phones is fiddly, so I frequently include “Copy to clipboard” buttons that populate the clipboard with a single touch.

Most operating system clipboards can carry multiple formats of the same copied data. That’s why you can paste content from a word processor in a way that preserves formatting, but if you paste the same thing into a text editor you’ll get the content with formatting stripped.

These rich copy operations are available in JavaScript paste events as well, which opens up all sorts of opportunities for HTML tools.

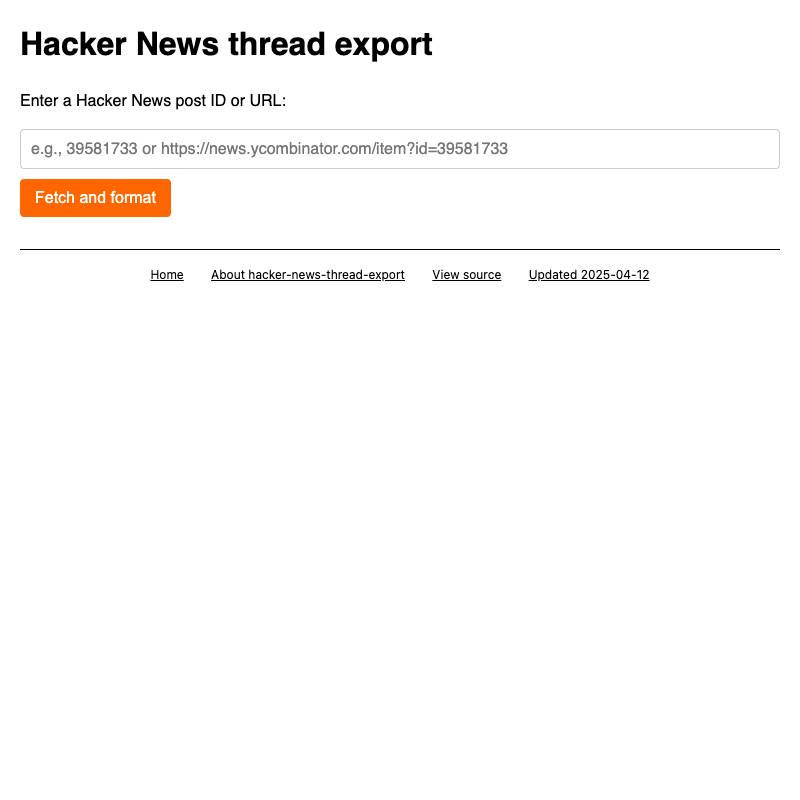

- hacker-news-thread-export lets you paste in a URL to a Hacker News thread and gives you a copyable condensed version of the entire thread, suitable for pasting into an LLM to get a useful summary.

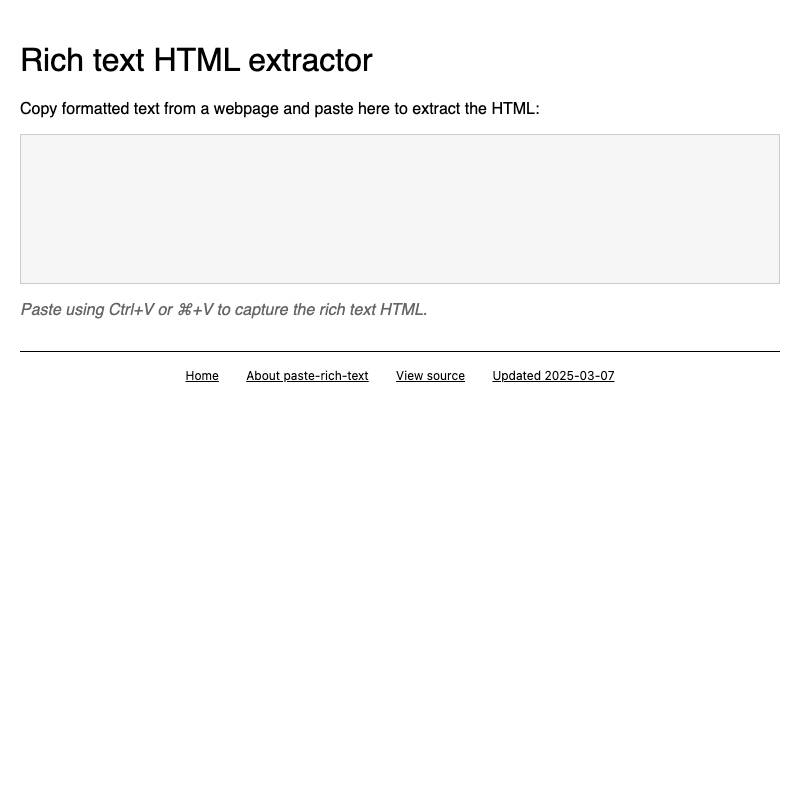

- paste-rich-text lets you copy from a page and paste to get the HTML—particularly useful on mobile where view-source isn’t available.

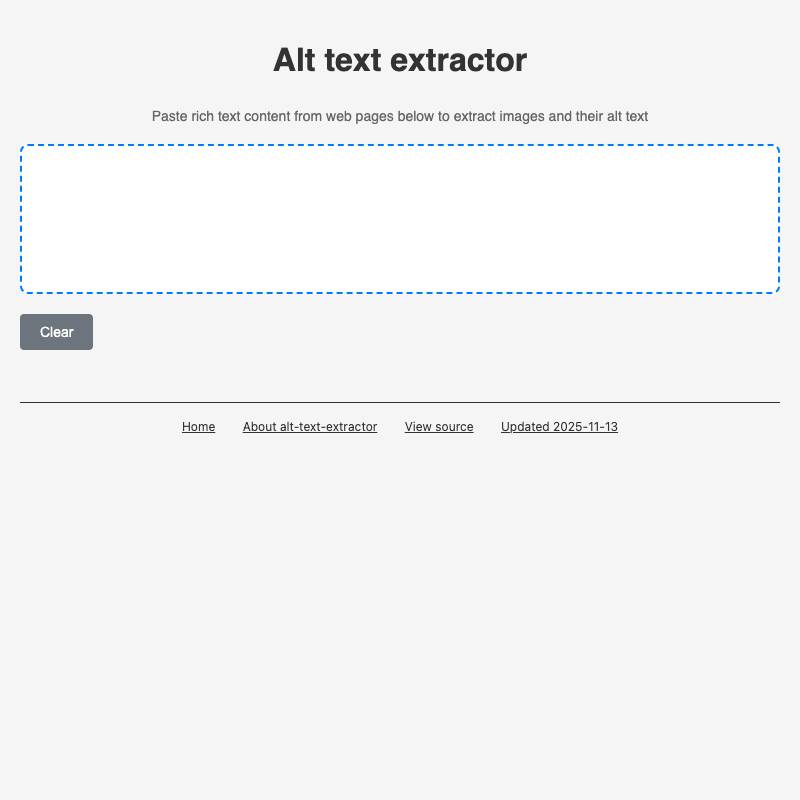

- alt-text-extractor lets you paste in images and then copy out their alt text.

Build debugging tools

The key to building interesting HTML tools is understanding what’s possible. Building custom debugging tools is a great way to explore these options.

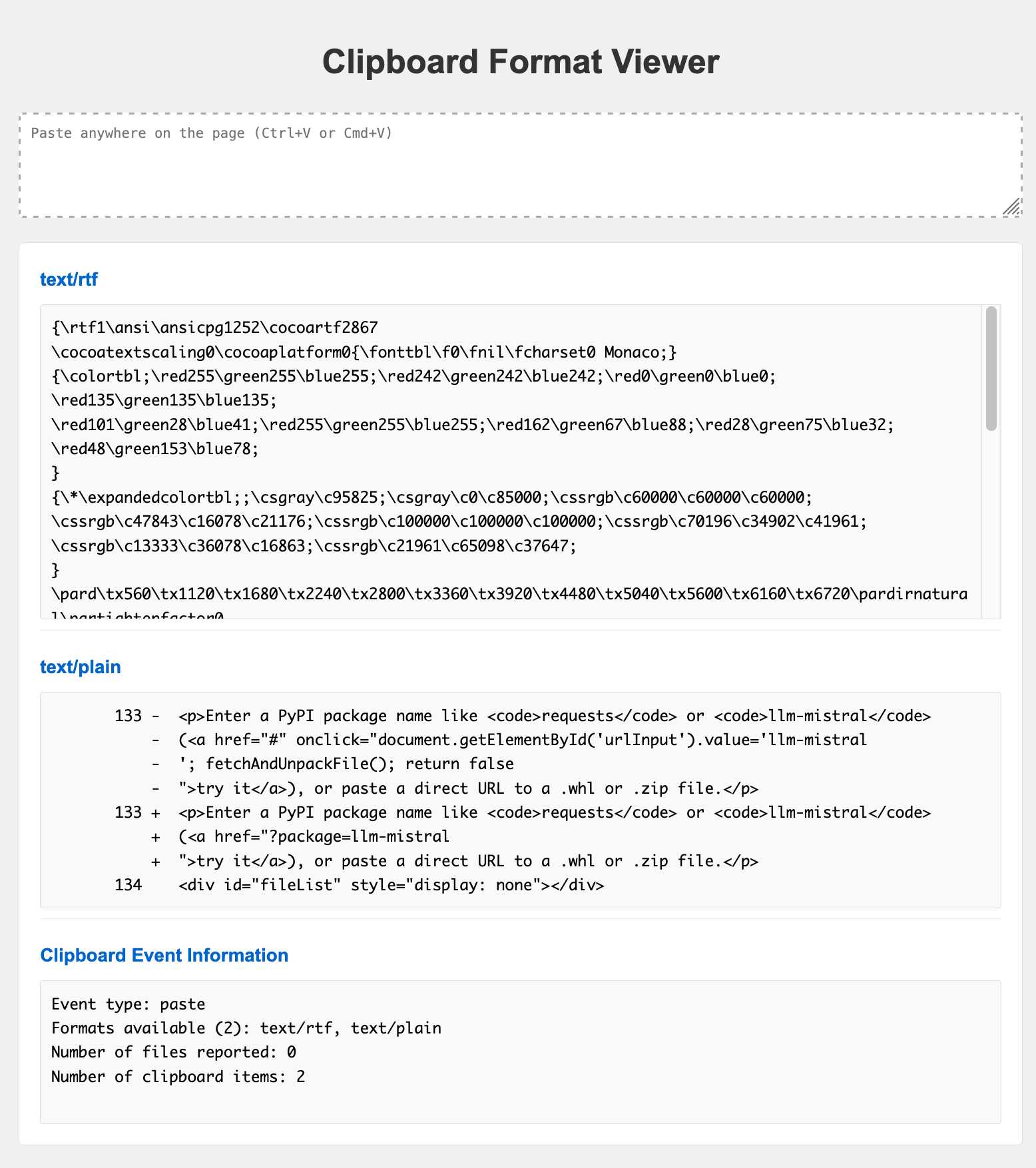

clipboard-viewer is one of my most useful. You can paste anything into it (text, rich text, images, files) and it will loop through and show you every type of paste data that’s available on the clipboard.

This was key to building many of my other tools, because it showed me the invisible data that I could use to bootstrap other interesting pieces of functionality.

More debugging examples:

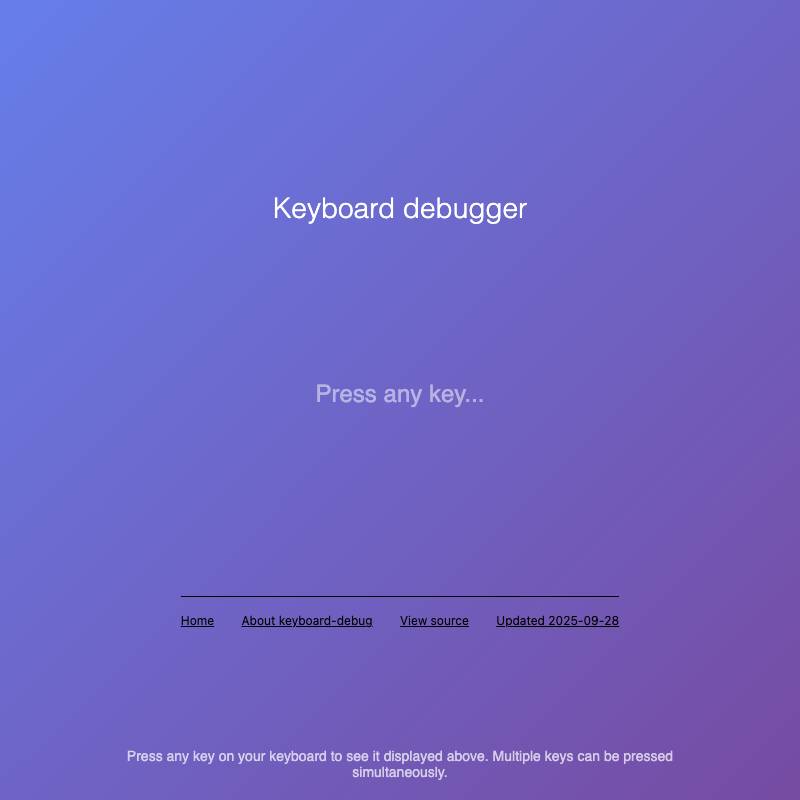

-

keyboard-debug shows the keys (and

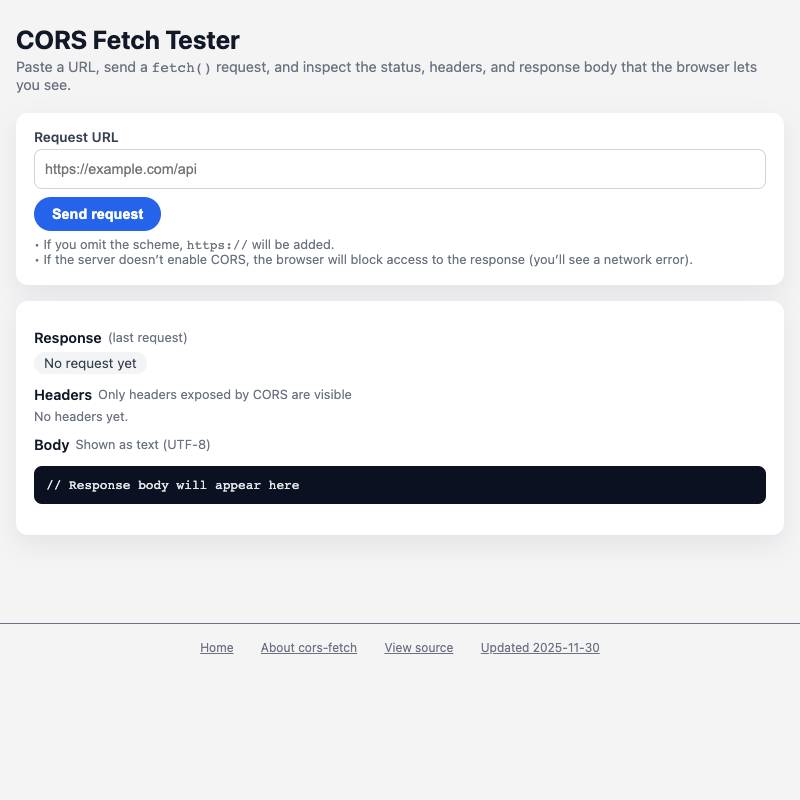

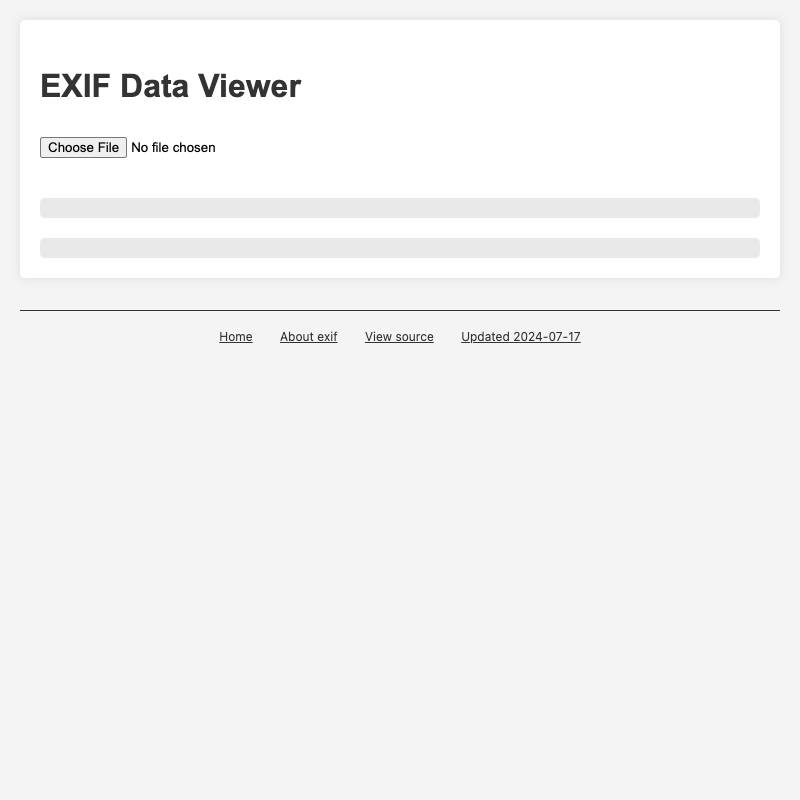

KeyCodevalues) currently being held down. - cors-fetch reveals if a URL can be accessed via CORS.

- exif displays EXIF data for a selected photo.

Persist state in the URL

HTML tools may not have access to server-side databases for storage but it turns out you can store a lot of state directly in the URL.

I like this for tools I may want to bookmark or share with other people.

- icon-editor is a custom 24x24 icon editor I built to help hack on icons for the GitHub Universe badge. It persists your in-progress icon design in the URL so you can easily bookmark and share it.

Use localStorage for secrets or larger state

The localStorage browser API lets HTML tools store data persistently on the user’s device, without exposing that data to the server.

I use this for larger pieces of state that don’t fit comfortably in a URL, or for secrets like API keys which I really don’t want anywhere near my server —even static hosts might have server logs that are outside of my influence.

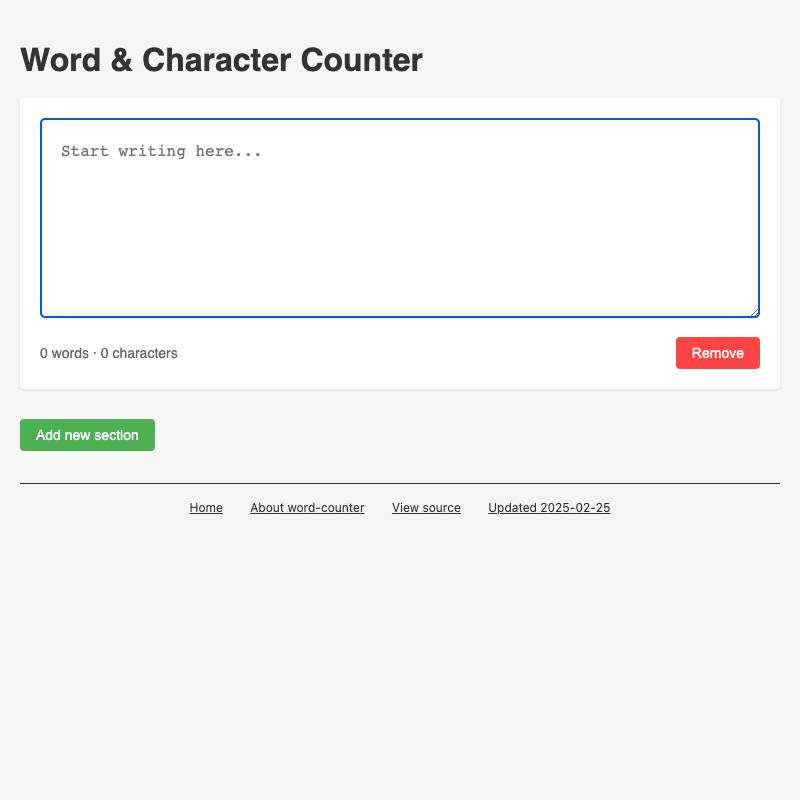

- word-counter is a simple tool I built to help me write to specific word counts, for things like conference abstract submissions. It uses localStorage to save as you type, so your work isn’t lost if you accidentally close the tab.

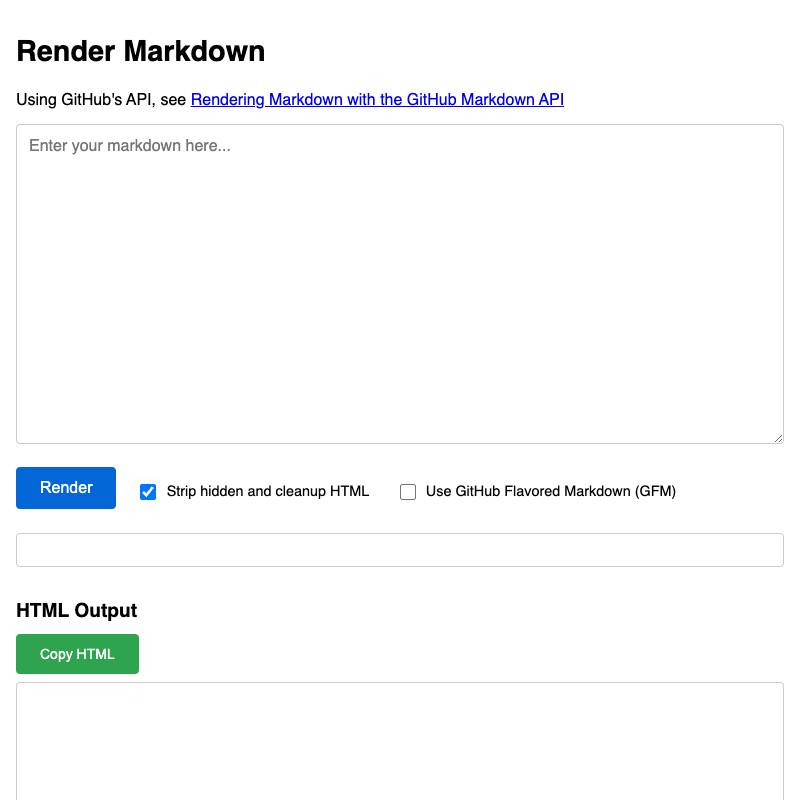

- render-markdown uses the same trick—I sometimes use this one to craft blog posts and I don’t want to lose them.

-

haiku is one of a number of LLM demos I’ve built that request an API key from the user (via the

prompt()function) and then store that inlocalStorage. This one uses Claude Haiku to write haikus about what it can see through the user’s webcam.

Collect CORS-enabled APIs

CORS stands for Cross-origin resource sharing. It’s a relatively low-level detail which controls if JavaScript running on one site is able to fetch data from APIs hosted on other domains.

APIs that provide open CORS headers are a goldmine for HTML tools. It’s worth building a collection of these over time.

Here are some I like:

- iNaturalist for fetching sightings of animals, including URLs to photos

- PyPI for fetching details of Python packages

- GitHub because anything in a public repository in GitHub has a CORS-enabled anonymous API for fetching that content from the raw.githubusercontent.com domain, which is behind a caching CDN so you don’t need to worry too much about rate limits or feel guilty about adding load to their infrastructure.

- Bluesky for all sorts of operations

- Mastodon has generous CORS policies too, as used by applications like phanpy.social

GitHub Gists are a personal favorite here, because they let you build apps that can persist state to a permanent Gist through making a cross-origin API call.

- species-observation-map uses iNaturalist to show a map of recent sightings of a particular species.

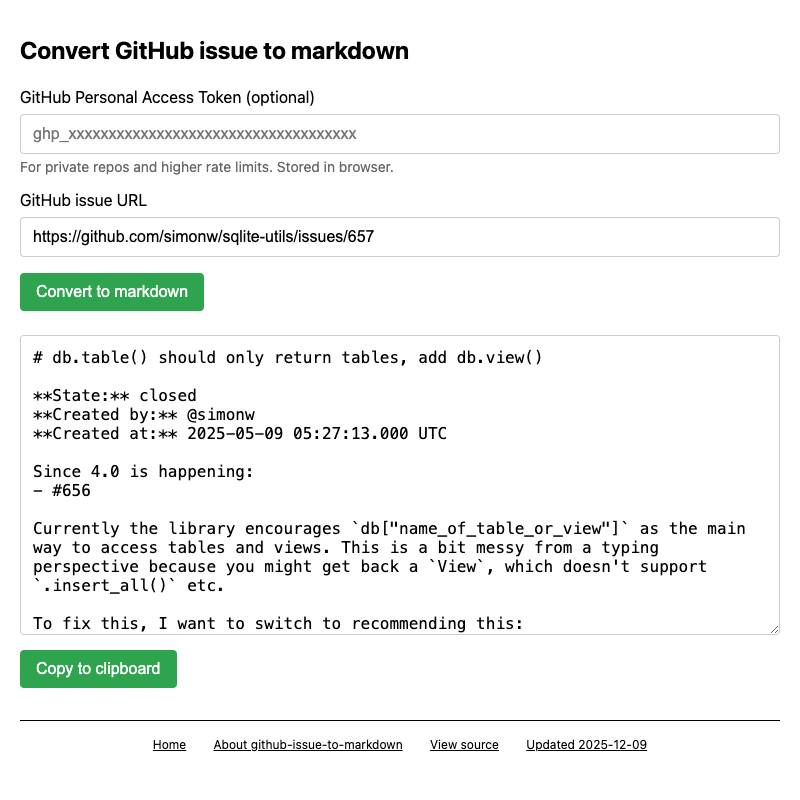

-

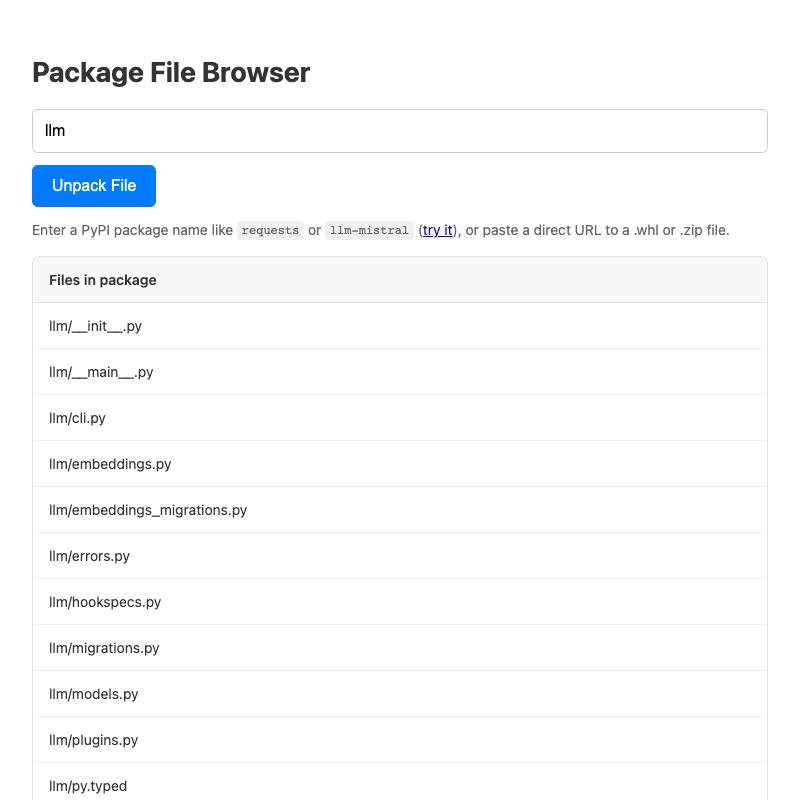

zip-wheel-explorer fetches a

.whlfile for a Python package from PyPI, unzips it (in browser memory) and lets you navigate the files. - github-issue-to-markdown fetches issue details and comments from the GitHub API (including expanding any permanent code links) and turns them into copyable Markdown.

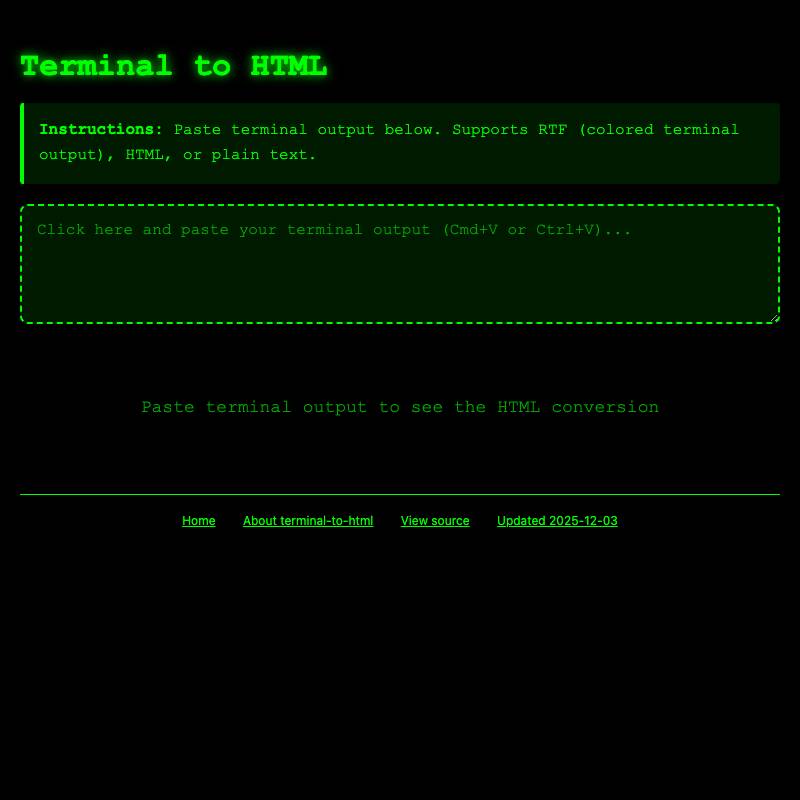

- terminal-to-html can optionally save the user’s converted terminal session to a Gist.

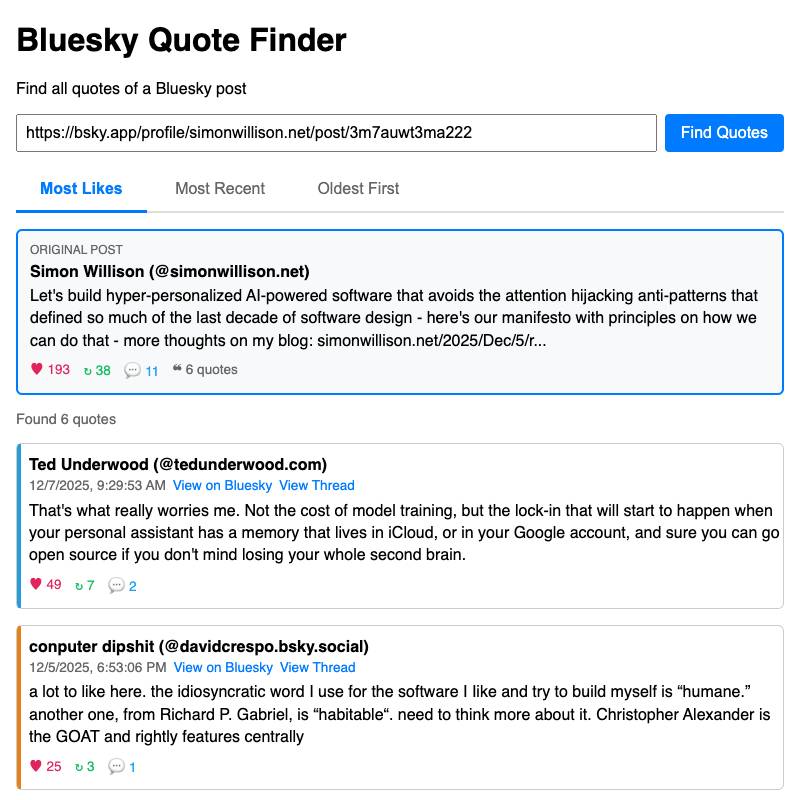

- bluesky-quote-finder displays quotes of a specified Bluesky post, which can then be sorted by likes or by time.

LLMs can be called directly via CORS

All three of OpenAI, Anthropic and Gemini offer JSON APIs that can be accessed via CORS directly from HTML tools.

Unfortunately you still need an API key, and if you bake that key into your visible HTML anyone can steal it and use to rack up charges on your account.

I use the localStorage secrets pattern to store API keys for these services. This sucks from a user experience perspective—telling users to go and create an API key and paste it into a tool is a lot of friction—but it does work.

Some examples:

- haiku uses the Claude API to write a haiku about an image from the user’s webcam.

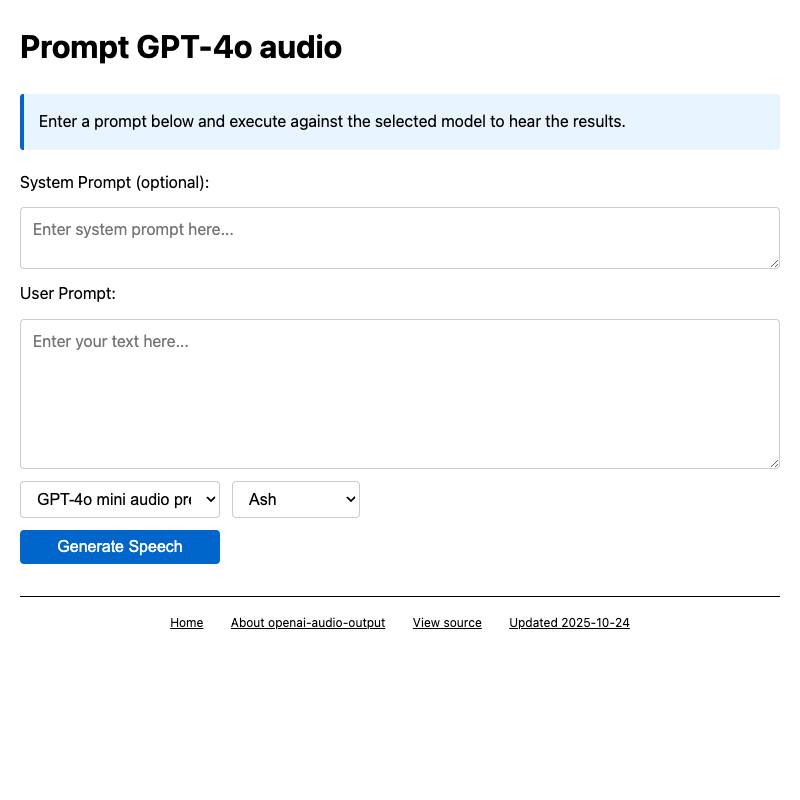

- openai-audio-output generates audio speech using OpenAI’s GPT-4o audio API.

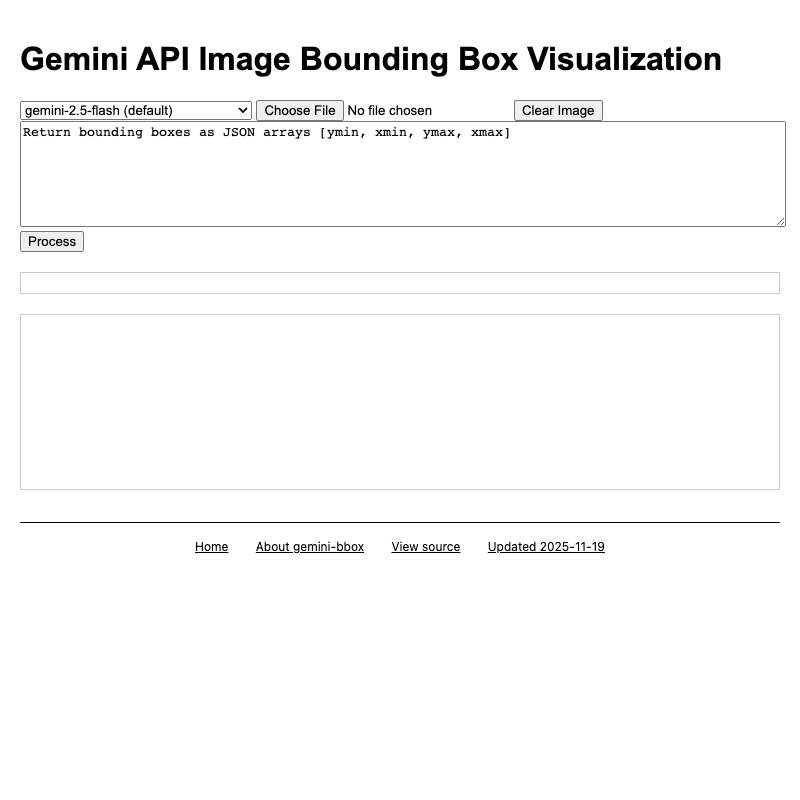

- gemini-bbox demonstrates Gemini 2.5’s ability to return complex shaped image masks for objects in images, see Image segmentation using Gemini 2.5.

Don’t be afraid of opening files

You don’t need to upload a file to a server in order to make use of the <input type="file"> element. JavaScript can access the content of that file directly, which opens up a wealth of opportunities for useful functionality.

Some examples:

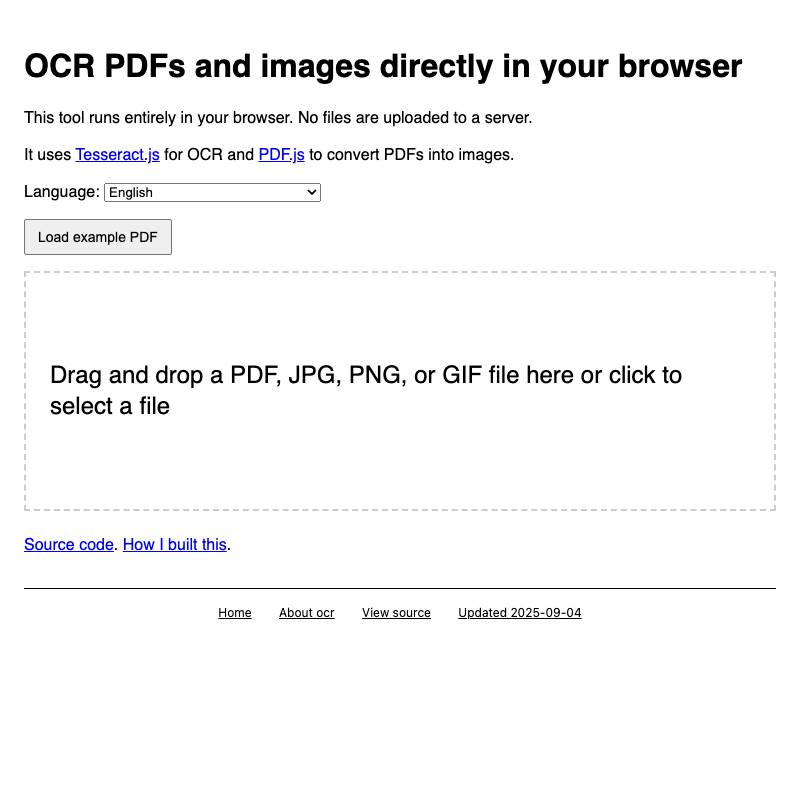

-

ocr is the first tool I built for my collection, described in Running OCR against PDFs and images directly in your browser. It uses

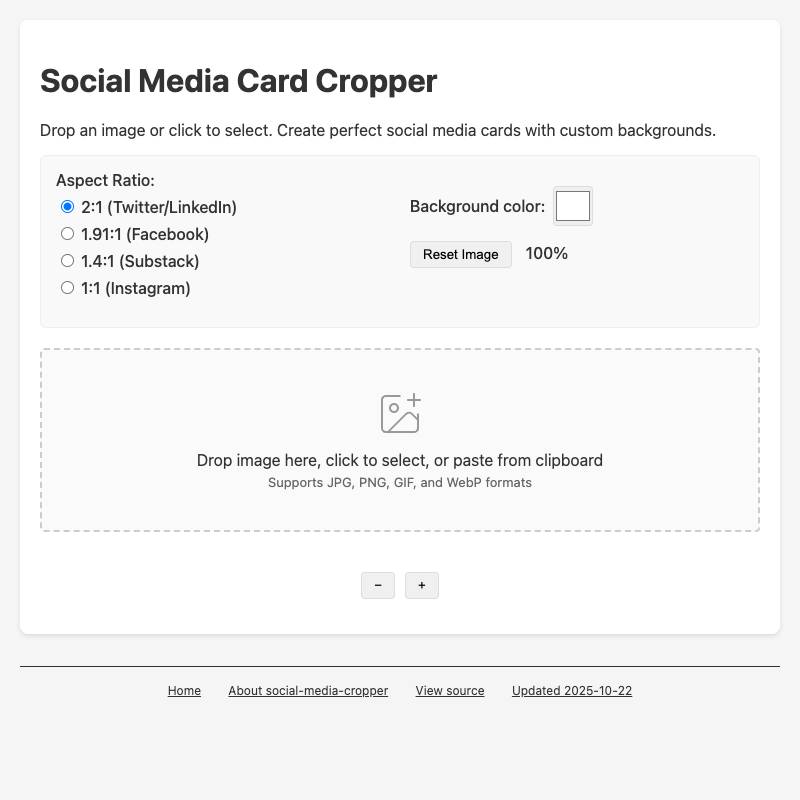

PDF.jsandTesseract.jsto allow users to open a PDF in their browser which it then converts to an image-per-page and runs through OCR. - social-media-cropper lets you open (or paste in) an existing image and then crop it to common dimensions needed for different social media platforms—2:1 for Twitter and LinkedIn, 1.4:1 for Substack etc.

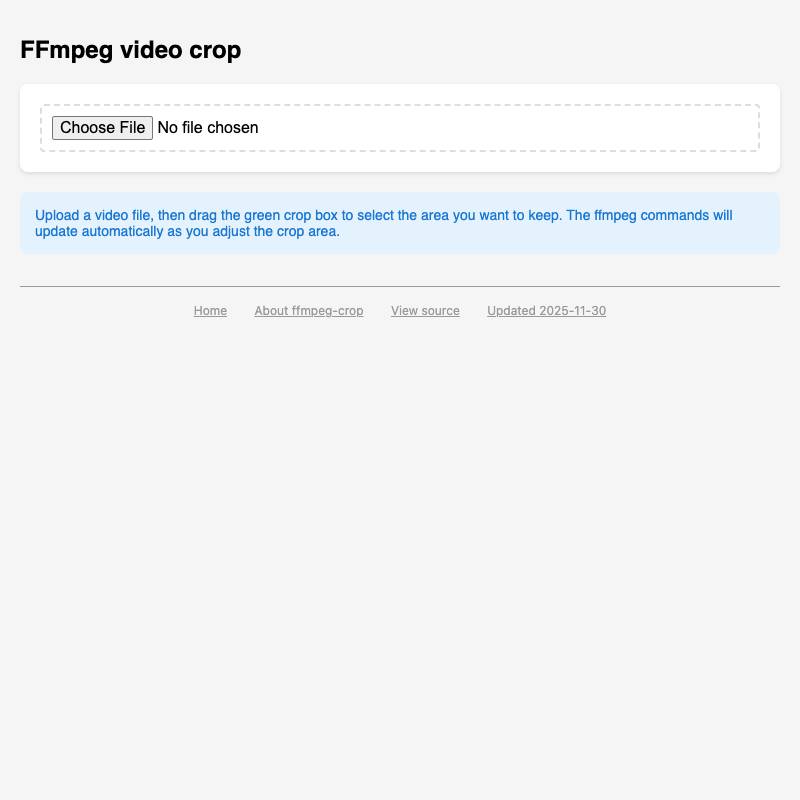

-

ffmpeg-crop lets you open and preview a video file in your browser, drag a crop box within it and then copy out the

ffmpegcommand needed to produce a cropped copy on your own machine.

You can offer downloadable files too

An HTML tool can generate a file for download without needing help from a server.

The JavaScript library ecosystem has a huge range of packages for generating files in all kinds of useful formats.

- svg-render lets the user download the PNG or JPEG rendered from an SVG.

- social-media-cropper does the same for cropped images.

- open-sauce-2025 is my alternative schedule for a conference that includes a downloadable ICS file for adding the schedule to your calendar. See Vibe scraping and vibe coding a schedule app for Open Sauce 2025 entirely on my phone for more on that project.

Pyodide can run Python code in the browser

Pyodide is a distribution of Python that’s compiled to WebAssembly and designed to run directly in browsers. It’s an engineering marvel and one of the most underrated corners of the Python world.

It also cleanly loads from a CDN, which means there’s no reason not to use it in HTML tools!

Even better, the Pyodide project includes micropip—a mechanism that can load extra pure-Python packages from PyPI via CORS.

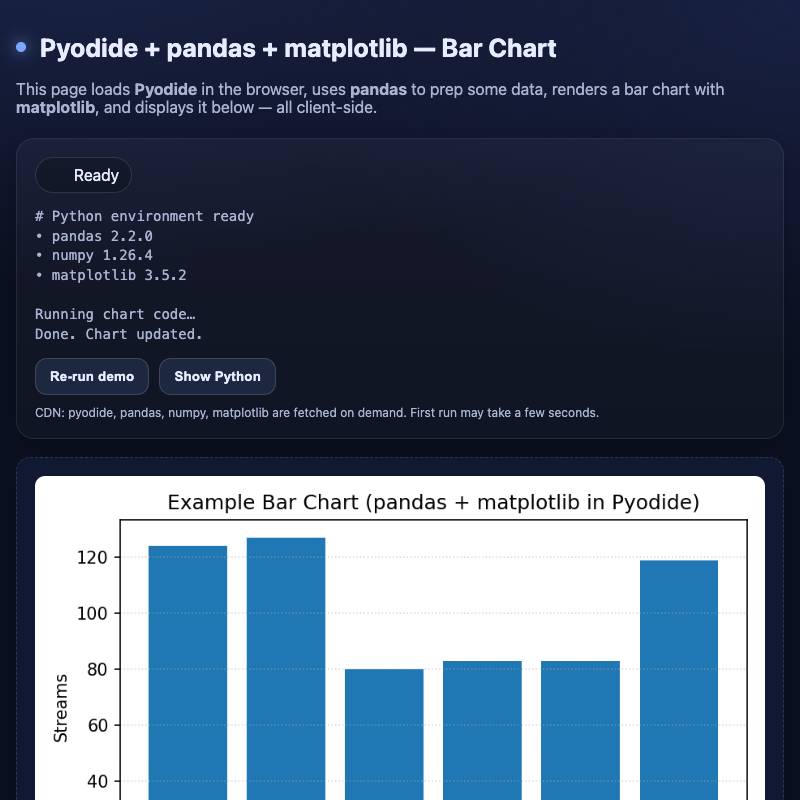

- pyodide-bar-chart demonstrates running Pyodide, Pandas and matplotlib to render a bar chart directly in the browser.

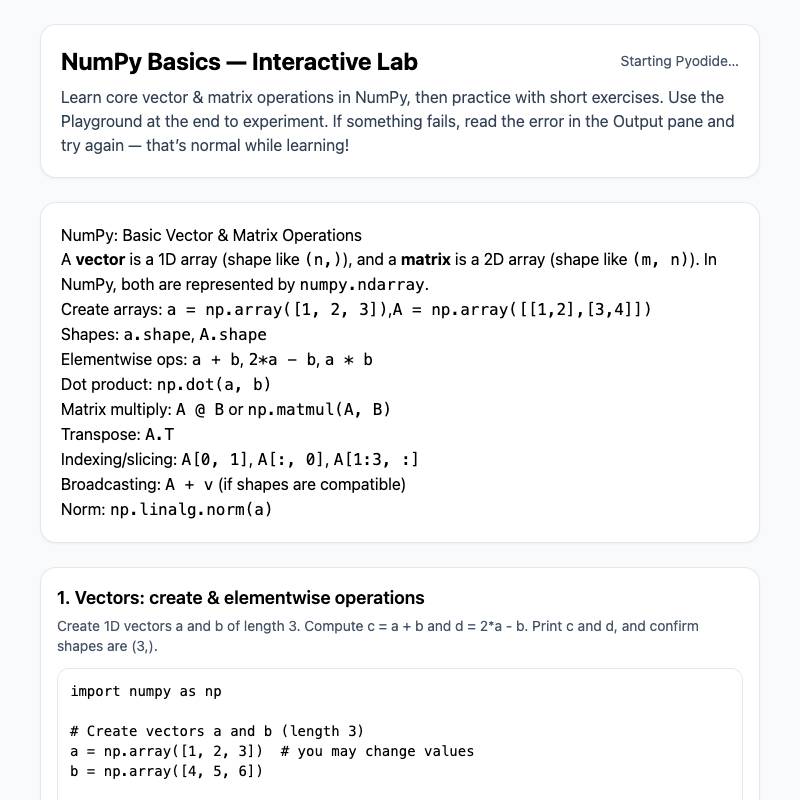

- numpy-pyodide-lab is an experimental interactive tutorial for Numpy.

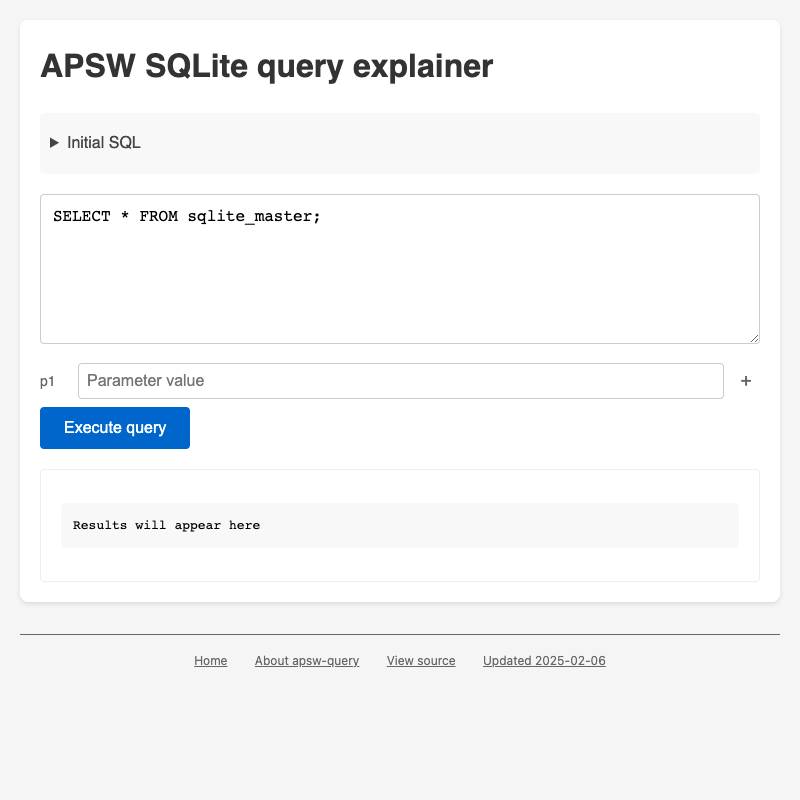

- apsw-query demonstrates the APSW SQLite library running in a browser, using it to show EXPLAIN QUERY plans for SQLite queries.

WebAssembly opens more possibilities

Pyodide is possible thanks to WebAssembly. WebAssembly means that a vast collection of software originally written in other languages can now be loaded in HTML tools as well.

Squoosh.app was the first example I saw that convinced me of the power of this pattern—it makes several best-in-class image compression libraries available directly in the browser.

I’ve used WebAssembly for a few of my own tools:

- ocr uses the pre-existing Tesseract.js WebAssembly port of the Tesseract OCR engine.

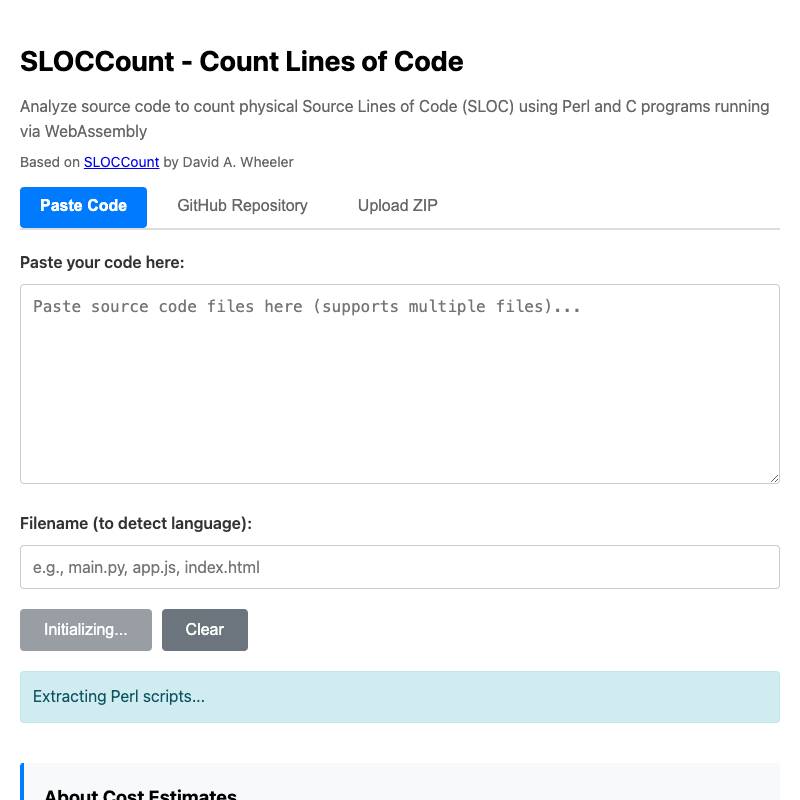

- sloccount is a port of David Wheeler’s Perl and C SLOCCount utility to the browser, using a big ball of WebAssembly duct tape. More details here.

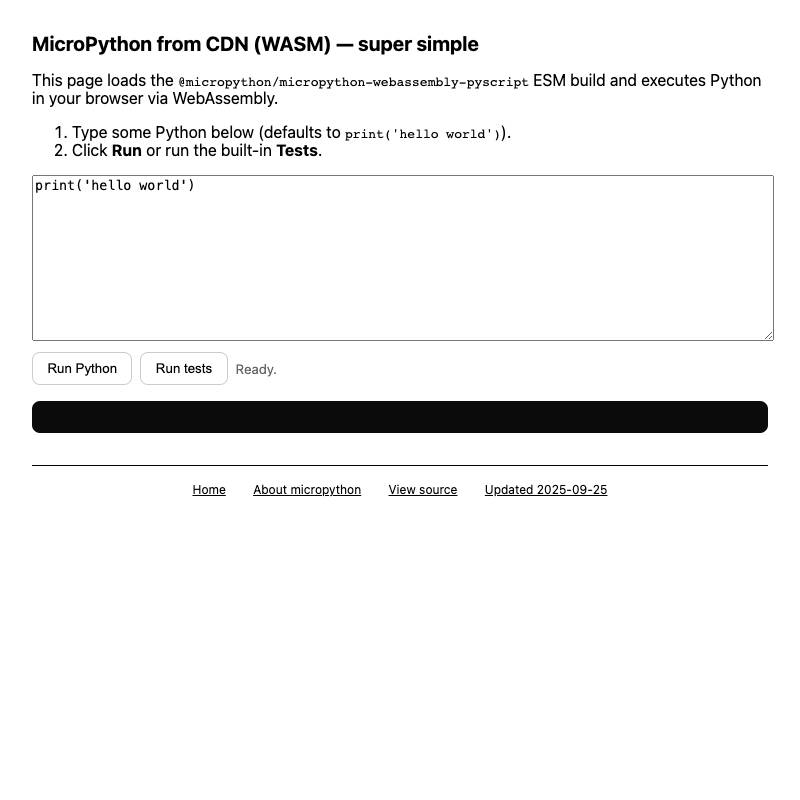

- micropython is my experiment using @micropython/micropython-webassembly-pyscript from NPM to run Python code with a smaller initial download than Pyodide.

Remix your previous tools

The biggest advantage of having a single public collection of 100+ tools is that it’s easy for my LLM assistants to recombine them in interesting ways.

Sometimes I’ll copy and paste a previous tool into the context, but when I’m working with a coding agent I can reference them by name—or tell the agent to search for relevant examples before it starts work.

The source code of any working tool doubles as clear documentation of how something can be done, including patterns for using editing libraries. An LLM with one or two existing tools in their context is much more likely to produce working code.

I built pypi-changelog by telling Claude Code:

Look at the pypi package explorer tool

And then, after it had found and read the source code for zip-wheel-explorer:

Build a new tool pypi-changelog.html which uses the PyPI API to get the wheel URLs of all available versions of a package, then it displays them in a list where each pair has a "Show changes" clickable in between them - clicking on that fetches the full contents of the wheels and displays a nicely rendered diff representing the difference between the two, as close to a standard diff format as you can get with JS libraries from CDNs, and when that is displayed there is a "Copy" button which copies that diff to the clipboard

Here’s the full transcript.

See Running OCR against PDFs and images directly in your browser for another detailed example of remixing tools to create something new.

Record the prompt and transcript

I like keeping (and publishing) records of everything I do with LLMs, to help me grow my skills at using them over time.

For HTML tools I built by chatting with an LLM platform directly I use the “share” feature for those platforms.

For Claude Code or Codex CLI or other coding agents I copy and paste the full transcript from the terminal into my terminal-to-html tool and share that using a Gist.

In either case I include links to those transcripts in the commit message when I save the finished tool to my repository. You can see those in my tools.simonwillison.net colophon.

Go forth and build

I’ve had so much fun exploring the capabilities of LLMs in this way over the past year and a half, and building tools in this way has been invaluable in helping me understand both the potential for building tools with HTML and the capabilities of the LLMs that I’m building them with.

If you’re interested in starting your own collection I highly recommend it! All you need to get started is a free GitHub repository with GitHub Pages enabled (Settings -> Pages -> Source -> Deploy from a branch -> main) and you can start copying in .html pages generated in whatever manner you like.

Bonus transcript: Here’s how I used Claude Code and shot-scraper to add the screenshots to this post.

More recent articles

- I vibe coded my dream macOS presentation app - 25th February 2026

- Writing about Agentic Engineering Patterns - 23rd February 2026

- Adding TILs, releases, museums, tools and research to my blog - 20th February 2026