54 posts tagged “jacob-kaplan-moss”

2025

Happy 20th birthday Django! Here’s my talk on Django Origins from Django’s 10th

Today is the 20th anniversary of the first commit to the public Django repository!

[... 8,994 words]If you’re new to tech, taking [career] advice on what works for someone with a 20-year career is likely to be about as effective as taking career advice from a stockbroker or firefighter or nurse. There’ll be a few things that generalize, but most advice won’t.

Further, even advice people with long careers on what worked for them when they were getting started is unlikely to be advice that works today. The tech industry of 15 or 20 years ago was, again, dramatically different from tech today.

— Jacob Kaplan-Moss, Beware tech career advice from old heads

2024

It feels like we’re at a bit of an inflection point for the Django community. [...] One of the places someone could have the most impact is by serving on the DSF Board. Like the community at large, the DSF is at a transition point: we’re outgrowing the “small nonprofit” status, and have the opportunity to really expand our ambition and reach. In all likelihood, the decisions the Board makes over the next year or two will define our direction and strategy for the next decade.

2025 DSF Board Nominations. The Django Software Foundation board elections are coming up. There are four positions open, seven directors total. Terms last two years, and the deadline for submitting a nomination is October 25th (the date of the election has not yet been decided).

Several community members have shared "DSF initiatives I'd like to see" documents to inspire people who may be considering running for the board:

- Sarah Boyce (current Django Fellow) wants a marketing strategy, better community docs, more automation and a refresh of the Django survey.

- Tim Schilling wants one big sponsor, more community recognition and a focus on working groups.

- Carlton Gibson wants an Executive Director, an updated website and better integration of the community into that website.

- Jacob Kaplan-Moss wants effectively all of the above.

There's also a useful FAQ on the Django forum by Thibaud Colas.

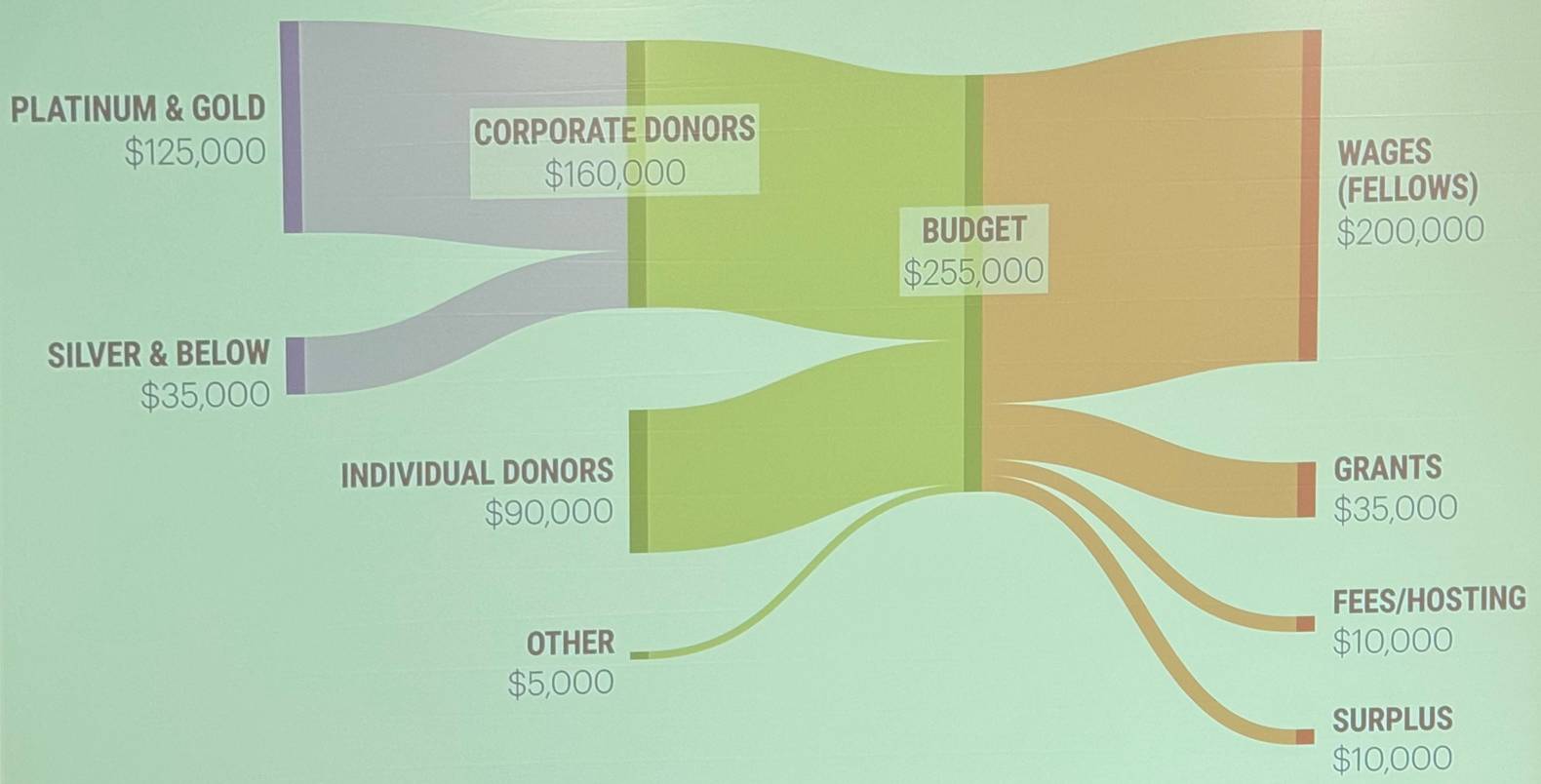

If we had $1,000,000…. Jacob Kaplan-Moss gave my favorite talk at DjangoCon this year, imagining what the Django Software Foundation could do if it quadrupled its annual income to $1 million and laying out a realistic path for getting there. Jacob suggests leaning more into large donors than increasing our small donor base:

It’s far easier for me to picture convincing eight or ten or fifteen large companies to make large donations than it is to picture increasing our small donor base tenfold. So I think a major donor strategy is probably the most realistic one for us.

So when I talk about major donors, who am I talking about? I’m talking about four major categories: large corporations, high net worth individuals (very wealthy people), grants from governments (e.g. the Sovereign Tech Fund run out of Germany), and private foundations (e.g. the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, who’s given grants to the PSF in the past).

Also included: a TIL on Turning a conference talk into an annotated presentation. Jacob used my annotated presentation tool to OCR text from images of keynote slides, extracted a Whisper transcript from the YouTube livestream audio and then cleaned that up a little with LLM and Claude 3.5 Sonnet ("Split the content of this transcript up into paragraphs with logical breaks. Add newlines between each paragraph.") before editing and re-writing it all into the final post.

Ethical Applications of AI to Public Sector Problems. Jacob Kaplan-Moss developed this model a few years ago (before the generative AI rush) while working with public-sector startups and is publishing it now. He starts by outright dismissing the snake-oil infested field of “predictive” models:

It’s not ethical to predict social outcomes — and it’s probably not possible. Nearly everyone claiming to be able to do this is lying: their algorithms do not, in fact, make predictions that are any better than guesswork. […] Organizations acting in the public good should avoid this area like the plague, and call bullshit on anyone making claims of an ability to predict social behavior.

Jacob then differentiates assistive AI and automated AI. Assistive AI helps human operators process and consume information, while leaving the human to take action on it. Automated AI acts upon that information without human oversight.

His conclusion: yes to assistive AI, and no to automated AI:

All too often, AI algorithms encode human bias. And in the public sector, failure carries real life or death consequences. In the private sector, companies can decide that a certain failure rate is OK and let the algorithm do its thing. But when citizens interact with their governments, they have an expectation of fairness, which, because AI judgement will always be available, it cannot offer.

On Mastodon I said to Jacob:

I’m heavily opposed to anything where decisions with consequences are outsourced to AI, which I think fits your model very well

(somewhat ironic that I wrote this message from the passenger seat of my first ever Waymo trip, and this weird car is making extremely consequential decisions dozens of times a second!)

Which sparked an interesting conversation about why life-or-death decisions made by self-driving cars feel different from decisions about social services. My take on that:

I think it’s about judgement: the decisions I care about are far more deep and non-deterministic than “should I drive forward or stop”.

Where there’s moral ambiguity, I want a human to own the decision both so there’s a chance for empathy, and also for someone to own the accountability for the choice.

That idea of ownership and accountability for decision making feels critical to me. A giant black box of matrix multiplication cannot take accountability for “decisions” that it makes.

Themes from DjangoCon US 2024

I just arrived home from a trip to Durham, North Carolina for DjangoCon US 2024. I’ve already written about my talk where I announced a new plugin system for Django; here are my notes on some of the other themes that resonated with me during the conference.

[... 1,470 words]uv under discussion on Mastodon. Jacob Kaplan-Moss kicked off this fascinating conversation about uv on Mastodon recently. It's worth reading the whole thing, which includes input from a whole range of influential Python community members such as Jeff Triplett, Glyph Lefkowitz, Russell Keith-Magee, Seth Michael Larson, Hynek Schlawack, James Bennett and others. (Mastodon is a pretty great place for keeping up with the Python community these days.)

The key theme of the conversation is that, while uv represents a huge set of potential improvements to the Python ecosystem, it comes with additional risks due its attachment to a VC-backed company - and its reliance on Rust rather than Python.

Here are a few comments that stood out to me.

As enthusiastic as I am about the direction uv is going, I haven't adopted them anywhere - because I want very much to understand Astral’s intended business model before I hook my wagon to their tools. It's definitely not clear to me how they're going to stay liquid once the VC money runs out. They could get me onboard in a hot second if they published a "This is what we're planning to charge for" blog post.

As much as I hate VC, [...] FOSS projects flame out all the time too. If Frost loses interest, there’s no PDM anymore. Same for Ofek and Hatch(ling).

I fully expect Astral to flame out and us having to fork/take over—it’s the circle of FOSS. To me uv looks like a genius sting to trick VCs into paying to fix packaging. We’ll be better off either way.

Even in the best case, Rust is more expensive and difficult to maintain, not to mention "non-native" to the average customer here. [...] And the difficulty with VC money here is that it can burn out all the other projects in the ecosystem simultaneously, creating a risk of monoculture, where previously, I think we can say that "monoculture" was the least of Python's packaging concerns.

I don’t think y’all quite grok what uv makes so special due to your seniority. The speed is really cool, but the reason Rust is elemental is that it’s one compiled blob that can be used to bootstrap and maintain a Python development. A blob that will never break because someone upgraded Homebrew, ran pip install or any other creative way people found to fuck up their installations. Python has shown to be a terrible tech to maintain Python.

Just dropping in here to say that corporate capture of the Python ecosystem is the #1 keeps-me-up-at-night subject in my community work, so I watch Astral with interest, even if I'm not yet too worried.

I'm reminded of this note from Armin Ronacher, who created Rye and later donated it to uv maintainers Astral:

However having seen the code and what uv is doing, even in the worst possible future this is a very forkable and maintainable thing. I believe that even in case Astral shuts down or were to do something incredibly dodgy licensing wise, the community would be better off than before uv existed.

I'm currently inclined to agree with Armin and Hynek: while the risk of corporate capture for a crucial aspect of the Python packaging and onboarding ecosystem is a legitimate concern, the amount of progress that has been made here in a relatively short time combined with the open license and quality of the underlying code keeps me optimistic that uv will be a net positive for Python overall.

Update: uv creator Charlie Marsh joined the conversation:

I don't want to charge people money to use our tools, and I don't want to create an incentive structure whereby our open source offerings are competing with any commercial offerings (which is what you see with a lost of hosted-open-source-SaaS business models).

What I want to do is build software that vertically integrates with our open source tools, and sell that software to companies that are already using Ruff, uv, etc. Alternatives to things that companies already pay for today.

An example of what this might look like (we may not do this, but it's helpful to have a concrete example of the strategy) would be something like an enterprise-focused private package registry. A lot of big companies use uv. We spend time talking to them. They all spend money on private package registries, and have issues with them. We could build a private registry that integrates well with uv, and sell it to those companies. [...]

But the core of what I want to do is this: build great tools, hopefully people like them, hopefully they grow, hopefully companies adopt them; then sell software to those companies that represents the natural next thing they need when building with Python. Hopefully we can build something better than the alternatives by playing well with our OSS, and hopefully we are the natural choice if they're already using our OSS.

We respect wildlife in the wilderness because we’re in their house. We don’t fully understand the complexity of most ecosystems, so we seek to minimize our impact on those ecosystems since we can’t always predict what outcomes our interactions with nature might have.

In software, many disastrous mistakes stem from not understanding why a system was built the way it was, but changing it anyway. It’s super common for a new leader to come in, see something they see as “useless”, and get rid of it – without understanding the implications. Good leaders make sure they understand before they mess around.

I think most people have this naive idea of consensus meaning “everyone agrees”. That’s not what consensus means, as practiced by organizations that truly have a mature and well developed consensus driven process.

Consensus is not “everyone agrees”, but [a model where] people are more aligned with the process than they are with any particular outcome, and they’ve all agreed on how decisions will be made.

Talking about Django’s history and future on Django Chat (via) Django co-creator Jacob Kaplan-Moss sat down with the Django Chat podcast team to talk about Django’s history, his recent return to the Django Software Foundation board and what he hopes to achieve there.

Here’s his post about it, where he used Whisper and Claude to extract some of his own highlights from the conversation.

Paying people to work on open source is good actually. In which Jacob expands his widely quoted (including here) pithy toot about how quick people are to pick holes in paid open source contributor situations into a satisfyingly comprehensive rant. This is absolutely worth your time—there’s so much I could quote from here, but I’m going to go with this:

“Many, many more people should be getting paid to write free software, but for that to happen we’re going to have to be okay accepting impure or imperfect mechanisms.”

“We believe that open source should be sustainable and open source maintainers should get paid!”

Maintainer: introduces commercial features “Not like that”

Maintainer: works for a large tech co “Not like that”

Maintainer: takes investment “Not like that”

2023

Should you give candidates feedback on their interview performance? Jacob provides a characteristically nuanced answer to the question of whether you should provide feedback to candidates you have interviewed. He suggests offering the candidate the option to email asking for feedback early in the interview process to avoid feeling pushy later on, and proposes the phrase “you failed to demonstrate...” as a useful framing device.

2021

Probably Are Gonna Need It: Application Security Edition (via) Jacob Kaplan-Moss shares his PAGNIs for application security: “basic security mitigations that are easy to do at the beginning, but get progressively harder the longer you put them off”. Plenty to think about in here—I particularly like Jacob’s recommendation to build a production-to-staging database mirroring solution that works from an allow-list of columns, to avoid the risk of accidentally exposing new private data as the product continues to evolve.

Finally, remember that whatever choice is made, you’re going to need to get behind it! You should be able to make a compelling positive case for any of the options you present. If there’s an option you can’t support, don’t present it.

Generally, product-aligned teams deliver better products more rapidly. Again, Conway’s Law is inescapable; if delivering a new feature requires several teams to coordinate, you’ll struggle compared to an org where a single team can execute on a new feature.

2020

Demos, Prototypes, and MVPs (via) I really like how Jacob describes the difference between a demo and a prototype: a demo is externally facing and helps explain a concept to a customer; a prototype is internally facing and helps prove that something can be built.

2019

My Python Development Environment, 2020 Edition (via) Jacob Kaplan-Moss shares what works for him as a Python environment coming into 2020: pyenv, poetry, and pipx. I’m not a frequent user of any of those tools—it definitely looks like I should be.

pinboard-to-sqlite (via) Jacob Kaplan-Moss just released the second Dogsheep tool that wasn’t written by me (after goodreads-to-sqlite by Tobias Kunze)—this one imports your Pinterest bookmarks. The repo includes a really clean minimal example of how to use GitHub actions to run tests and release packages to PyPI.

2010

What to do when PyPI goes down. My deployment scripts tend to rely on PyPI these days (they install dependencies in to a virtualenv) which makes me distinctly uncomfortable. Jacob explains how to use the PyPI mirrors that are starting to come online, but that won’t help if the PyPI listing links to an externally hosted file which starts to 404, as happened with the python-openid package quite recently (now fixed). The comments on the post discuss workarounds, including hosting your own PyPI mirror or bundling tar.gz files of your dependencies with your project.

jacobian’s django-deployment-workshop. Notes and resources from Jacob’s 3 hour Django deployment workshop at PyCon, including example configuration files for Apache2 + mod_wsgi, nginx, PostgreSQL and pgpool.

2009

Writing good documentation (part 1). Jacob explains some of the philosophy behind Django’s documentation. Topical guides are particularly interesting—many projects skip them (leaving books to fill the gap) but they fill an essential gap between tutorials and low-level reference documentation.

Python is Unix. Jacob ports Ryan Tomayko’s simple prefork network server to Python.

Years ago, Alex Russell told me that Django ought to be collecting CLAs. I said "yeah, whatever" and ignored him. And thus have spent more than a year gathering CLAs to get DSF's paperwork in order. Sigh.

Twenty questions about the GPL. Jacob kicks off a fascinating discussion about GPLv3.

geocoders. A fifteen minute project extracted from something else I’m working on—an ultra simple Python API for geocoding a single string against Google, Yahoo! Placemaker, GeoNames and (thanks to Jacob) Yahoo! Geo’s web services.

REST worst practices. Jacob Kaplan-Moss’ thoughts on the characteristics of a well designed Django REST API library, from November 2008.

Developing Django apps with zc.buildout. Jacob went ahead and actually documented one of Python’s myriad of packaging options.

django-shorturls. Jacob took my self-admittedly shonky shorter URL code and turned it in to a proper reusable Django application.